Who’s awake in the woods at night? New study analyses the diel activity of carnivores

Who’s awake in the woods at night? New study analyses the diel activity of carnivores

The coexistence of wildlife and people in Europe's human-dominated landscape is a complex phenomenon. Protected areas are relatively small and they intermingle with areas of high human disturbance. This leads animals to use various adaptation mechanisms, including increasing their nocturnal activity. The recent study supported by our project analyses for the first time the diurnal activity of wolves and lynx along a gradient of human disturbance to reveal the correlation between anthropogenic pressure and animals’ temporal behavior.

A growing human presence in wildlife areas is particularly critical for large carnivores with large home ranges, such as the wolf and Eurasian lynx. Increasing nocturnal behaviour is one of the strategies that allows these animals to avoid risky interactions with humans. This behavioural adaptation mechanism has been described before. However, the new study is the first attempt to analyse the diurnal activity of the two carnivore species in a number of areas that differ in character and intensity of human presence – from areas of intense anthropogenic pressure to those where human activity is highly restricted.

Understanding the behaviour of large carnivores and the factors that cause them to change their mode of living is important from a number of perspectives. On the one hand, if human disturbance causes carnivores to shift their activity to the nocturnal period, this could affect their interactions with prey, with potentially significant consequences for the ecosystem. On the other hand, in human-dominated landscapes, nocturnal behaviour reduces negative human-animal interactions and thus benefits the conservation of carnivores by enabling their conflict-free coexistence.

Previous studies have shown that both wolves and lynx are predominantly nocturnal in Europe and have suggested that anthropogenic factors may influence their temporal behaviour. However, no attempt has been made to analyse the diurnal activity of carnivores in the context of a comparison between areas with different levels of anthropogenic pressure.

The authors of the new study suggested that both wolves and lynx would be more active during the day under conditions of low anthropogenic pressure and the probability of being active at night would rise as human disturbance increased. To test this hypothesis, the researchers analysed images from camera traps deployed at nine sites in six European countries with a gradient of anthropogenic pressure.

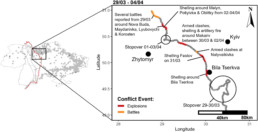

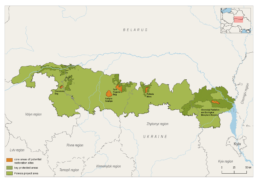

Remarkably, two of these sites are located in Polesia: the Ukrainian part of the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone and Pripyat-Polesia in Belarus. The lowest indices of human disturbance were expected to be found in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone (Ukraine), which was used as a baseline for wolf and lynx behaviour. Human activity in this area is extremely low due to decades of restricted human access following the Chornobyl nuclear accident in 1986. Camera trap data was also collected in central Belarusian Pripyat-Polesia (Belarus), Białowieża Primeval Forest (Poland), Tuchola Forest Complex (Poland), Bieszczady National Park (Poland), Skolivski Beskydy National Park (Ukraine), Bavarian Forest National Park (Germany), Plitvice Lakes National Park (Croatia) and Maremma Regional Park (Italy). All these areas are disturbed to a greater or lesser extent by various anthropogenic factors and their combinations, such as forestry, hunting, agriculture or tourism.

The data collected covers several years, from 2014 to 2022, focusing on the period from September to April, when large carnivores are usually monitored. Cameras were deployed along forest roads and trails used both by carnivores and people.

The analysed data set comprised more than 71,000 independent encounters, including 2,430 of wolves, 934 of lynx, 8,585 of prey species, and 59,408 of humans. The highest rate of human encounter was recorded in the Bavarian Forest National Park, while the lowest was in the Skolivski Beskydy National Park, followed by the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone.

The researchers found out that wolves in all the study sites were rather nocturnal than diurnal. As expected, wolves in our baseline study area in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone showed the highest levels of daytime activity. In Skolivski Beskydy and Białowieża National Parks, wolves were the second-most diurnal, while wolves in Belarusian Pripyat-Polesia were the most nocturnal. It is noteworthy that the latter area is characterised by the highest level of anthropogenic pressure and wolf hunting is allowed all year round. Apart from the human encounter rate, no human disturbance factors, such as human population or road density, explained higher activity of wolves at nighttime at the landscape level.

Lynx were consistently nocturnal in all study sites. However, lynx in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone were not the most likely to be observed at daytime: lynx in the Plitvice Lakes National Park had the highest probability of observation during the day, while lynx in the Bavarian Forest National Park were the most nocturnal. The data obtained indicates that the nocturnal habit of the lynx does not depend on the type and level of human disturbance.

The results of the study show that wolves change their temporal behavior in response to human pressure, but lynx don’t. This is most likely due to differences in their predation ecology.

Although they often prey on the same species, wolves and lynx have different hunting strategies. As cursorial predators, wolves rely on pursuit tactics. However, they can also use the stalk and ambush strategy, which is most effective in low light conditions. Wolves’ hunting success is generally highest at twilight, but it is likely that some wolves have improved their hunting success at daytime. In addition, the social behaviour of wolves can also influence their way of life, as they can hunt alone or in packs. As a predominantly solitary, ambush predator, the lynx fits well into the nocturnal-crepuscular niche because darkness allows it to implement its hunting strategy most effectively.

Areas of restricted human access in Europe are unlikely to expand in the near future. However, populations of large carnivores such as wolves and lynx are increasing and recolonising areas where they were previously extinct. This allows researchers to predict that populations of such species will continue to exhibit predominantly nocturnal behaviour in areas with high human presence, in order to minimise potentially dangerous interactions with humans. Understanding the daily activities of animals will help to develop effective strategies for carnivore conservation and the creation of a landscape of conflict-free coexistence between humans and wildlife.

Adam Francis Smith, Research and Monitoring Coordinator at the Frankfurt Zoological Society, one of the study’s authors:

“The most valuable result to me is managing people’s expectations of large carnivores. It is common to assume that wolves are just creatures of night time, but ultimately it is our impacts on the landscape, mostly during daytime, which confine them to night. Wolves are intelligent and adaptable to different human pressures. However, Eurasian lynx are mostly ambush predators, so being active at night fits their predation mode very well. Ultimately, this type of study wouldn’t be possible without access to great colleagues and data from a wide range of areas.

If we confine wolves to night because of human disturbance during the day, we can expect different behaviours. If we want to allow the full range of wolf behaviours, or in other words, to allow them to choose when to be active, we must decrease our disturbance in time as well as space. So, the most obvious next steps are to look at how these human disturbances influence other aspects of wolf and lynx biology. For example, is the hunting success lower in more nocturnal populations? What about the size of family groups? These are important questions for finding the balance between human disturbance and the capabilities and persistence of large carnivores in Europe.”

Smith, Adam & Kasper, Katharina & Lazzeri, Lorenzo & Schulte, Michael & Kudrenko, Svitlana & Say-Sallaz, Elise & Churski, Marcin & Shamovich, Dmitry & Obrizan, Serhii & Domashevsky, Serhii & Korepanova, Kateryna & Bashta, Andriy-Taras & Zhuravchak, Rostyslav & Gahbauer, Martin & Pirga, Bartosz & Fenchuk, Viktar & Kusak, Josip & Ferretti, Francesco & Kuijper, D.P.J. & Heurich, Marco. (2024). Reduced human disturbance increases diurnal activity in wolves, but not Eurasian lynx. Global Ecology and Conservation. e02985. DOI:10.1016/j.gecco.2024.e02985

Re-encountering Polesia’s nature and people: summer expedition of the Frankfurt Zoological Society

Re-encountering Polesia’s nature and people: summer expedition of the Frankfurt Zoological Society

At the end of July, a team from the Frankfurt Zoological Society visited several protected areas in Ukrainian Polesia. They met with local conservationists to discuss their current work and most pressing needs, got acquainted with some valuable natural objects, and inspected the areas waiting for consistent and professional restoration.

The cooperation between the Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS) and protected areas of Ukrainian Polesia has already become a good tradition. FZS has been providing material, technical and financial support to eight national parks and strict nature reserves in the region for several years. In particular, biodiversity monitoring has been carried out in a number of protected areas in Polesia, including using novel methods such as camera trapping and acoustic monitoring. Management plans have been developed for several protected areas in Ukrainian Polesia with the participation of FZS. A number of protected areas also received vehicles and other equipment to make the daily work of the staff easier and more efficient. Following Russia’s full-scale military invasion of Ukraine, some protected areas received additional funding to provide shelter for internally displaced people.

Michael Brombacher, Head of FZS Europe Department:

Polesia is one of the largest and most intact floodplain landscapes in Europe with numerous rivers, peatlands and lakes. It is home to large mammals such as moose and lynx, and is important for migratory birds. But the wetlands are also vital to the people of the region, providing food and possessing great tourism potential. Polesia is well protected by a number of nature reserves and national parks, some of which have only recently been established, such as the Pushcha Radzivila National Park. FZS stands by the protected areas in the Carpathians and Polesia during the current difficult economic period caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In doing so, we are helping the dedicated staff of the protected areas to continue their important work – keeping Ukraine’s nature intact.

At the end of July, a team from the Frankfurt Zoological Society took part in another expedition to national nature parks and nature reserves in Polesia to learn about their work and understand the needs of the institutions.

Despite a lack of staff, scarce funds and the war in the country, the conservationists of Ukrainian Polesia are doing their best to protect and promote the local nature and to tackle the various problems and challenges they face in their work. For example, rubbish collection points in the Nobelskyi National Park help to keep the recreation areas clean. Bird watching towers in the Prypiat-Stokhid National Park and the Cheremskyi Strict Nature Reserve attract nature lovers. An ornithological trail above the water in the Poliskyi Strict Nature Reserve is designed for eco-educational purposes and makes it possible to combine recreation and nature observation.

Volodymyr Dikovytskyi, Director of the Nobelskyi National Park:

Without the support from FZS, the Nobelskyi National Park would not be able to function at all! And this is no exaggeration. Since the establishment of the Nobelskyi National Park in 2019 and to this day, 80% of the material and technical base that the park has, including machinery, equipment, supplies, etc., have been provided by the Frankfurt Zoological Society.

Every encounter with Polesia’s intact wilderness is energising and inspiring. This visit was no exception! The participants of the expedition enjoyed the view of the vast wetlands and forests, the purity and freshness of the lakes. They observed the nesting sites of the rare Greater Spotted Eagle and visited the Juzefin Oak, believed to be one of the oldest trees in Ukraine.

While in some places the beauty and power of Polesia’s nature is striking, in others it is clear how much it needs help when it suffers from human activity. The participants of the expedition paid particular attention to the natural sites that have been affected by various anthropogenic factors. In the Nobelskyi National Park, for example, the guests were shown the traces of amber mining. This illegal activity has led to a serious disturbance of the hydrological regime, massive deforestation and the destruction of the fertile soil layer. Such areas can be recultivated, but it takes a lot of special knowledge, effort and certainly time.

Drevlianskyi Strict Nature Reserve and Pushcha Radzivila National Park are suffering from wildfires – the expedition participants saw large areas of forest destroyed by flames. Scientists point out that forests become less resistant to devastating wildfires when hydrological regimes are disturbed. This means that restoring the region’s wetlands can help to prevent large forest fires, which are one of the main threats to Polesia’s natural environment.

Water is the blood of Polesia, an inseparable part of its precious wetland ecosystems. Unfortunately, Polesia is losing water: this process is still going on due to intensive drainage in the past, especially in the mid-20th century. For example, in the Rivnenskyi Strict Nature Reserve, old drainage systems still influence the hydrological regime of the area and disturb the local ecosystems. Blocking the drainage channels would help to restore the surrounding wetlands to a near-natural state.

In the Poliskyi Strict Nature Reserve and the Chornobyl Radiation and Ecological Biosphere Reserve, the consequences of the alteration of the Zholobnytsia and Uzh riverbeds are obvious. In their natural state, Polesian rivers meander through the landscape, which creates favourable conditions for sustainable and harmonious wetland ecosystems. However, this harmony is destroyed when people start to straighten rivers for economic purposes – floodplain ecosystems are disturbed, and mires and peatlands are drained. Reverse transformation of riverbeds is possible, though labour- and resource-consuming.

Ecosystem restoration is now the focus of FZS’s work in Polesia. Some time ago, five drained wetlands were selected for further rewetting. And this summer’s expedition was another opportunity to compare notes with partners, identify priority tasks and needs, synchronise efforts and make the work on the ground more efficient.

Bird's-eye view of the warzone: the armed conflict in Ukraine impacts seasonal migration

Bird's-eye view of the warzone: the armed conflict in Ukraine impacts seasonal migration

Polesia is a stronghold for many rare species, including the Greater Spotted Eagle, which is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 20% of the European population of this species breeds in Polesia. No wonder that these birds have been in the spotlight since the beginning of our project. To learn more about their behaviour, migration patterns and wintering grounds, we tagged more than 20 Greater Spotted Eagles with GPS transmitters as part of our project. No one could have even imagined that the data obtained in this way would be used to analyse the impact of a bloody military conflict on these rare birds.

On the 24th of February, 2022, the Russian Federation started its military invasion of Ukraine. And on the 3rd of March, the first of 19 GPS-tagged Greater Spotted Eagles began arriving in Ukraine from the south, on their annual migration route to breeding grounds in the Belarusian part of Polesia. Meanwhile, military activity was spreading, affecting more and more areas. Although shocked by the events, researchers realised that this was a rare opportunity to obtain information of unique scientific importance. Wars obviously have an impact on wildlife – both directly, via mortality and environmental damage, and in many ways indirectly. But it is always difficult and dangerous to study these processes, let alone obtain real-time data. To date, most such studies have focused on sedentary species living in areas close to military training sites. At the same time, the impact of military conflicts on migratory birds has been poorly understood, despite the fact that the world’s major migratory corridors cross several active military conflict zones.

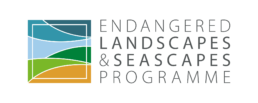

The researchers tracked the migration routes of GPS-tagged Greater Spotted Eagles in the spring of 2022 and then correlated this information with data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) project. They found out that the birds showed typical migratory behaviour before arriving in Ukraine. However, once they reached the active war zone, they started exhibiting different behaviour compared to previous years.

Prior to 2022, 90% of the birds observed stopped over in Ukraine on their way to their breeding grounds, whereas in 2022 only a third of the birds stopped over at the common sites.

The Greater Spotted Eagles also showed significant route deviations.In addition, they migrated 20-30% slower and their migration through Ukraine took longer than in previous years (25% longer for females and 50% longer for males). As a result, the birds arrived at their breeding grounds later than usual, and the energetic cost of the migration increased. The authors of this research suppose that the changes in the birds`behavior caused by the military conflict could have sublethal fitness effects on the Greater Spotted Eagles.

The authors of the study cite a female Greater Spotted Eagle nicknamed Denisa as an example of non-typical migration behavior in spring 2022. She was exposed to numerous war events. After witnessing artillery fire and explosions along her route, she moved westwards to avoid crossing active conflict zones. The graph shows Denisa’s migration route and the war events she faced on her way.

Previous studies have shown that numerous and varied anthropogenic disturbances, especially those that are unexpected, can cause severe and prolonged stress that significantly alters the behaviour of wildlife. However, armed conflicts involving shelling and explosions, mining, heavy traffic, human migration, direct habitat destruction, wildfires and many more far exceed any other anthropogenic activity in terms of intensity. Such extreme disturbance can potentially have long-term effects on sensitive Greater Spotted Eagles, causing deterioration in their body condition and affecting the reproductive success of the birds breeding in and around conflict zones. This is particularly important given that their breeding success is comparatively low on average.

The authors of the paper emphasise that human conflicts can have serious direct and indirect effects on migratory species, not only in Ukraine but also in other war zones along globally important migratory routes, which could be detrimental to hundreds of endangered species and millions of migratory birds.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

The Chornobyl Exclusion Zone: Polesia’s complex legacy

The Chornobyl Exclusion Zone: Polesia’s complex legacy

Polesia is known as a vast area of rich and diverse wilderness, however, not everyone realises that it was this very land that experienced one of the worst ecological disasters in history. It is Polesia that hosts the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone – the abandoned area created as a result of the sadly remembered nuclear accident. The complicated processes that have been taking place there for almost four decades, including the unguided rewilding of the abandoned areas and the lasting impact of radioactive contamination, continue to attract the attention of scientists and conservationists.

On 26 April 1986, a terrible accident occurred at the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant. As a result of an explosion, one of the nuclear units was destroyed. This led to the release of radioactive contaminants that quickly spread across the territories of the former Soviet Union and Europe. More than 115,000 people had to leave their homes in the 470,000-hectare area around the plant because of the severe contamination. This still uninhabited area, known as the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone (CEZ), is shared by Ukraine and Belarus. It is unevenly contaminated with radionuclides, including strontium, caesium, aluminium and plutonium, while many other radionuclides have already decayed. A special concrete confinement was built over the destroyed nuclear unit of the power plant to prevent further leakage of radioactive material.

In 1988, the Polesia State Radioecological Reserve was founded in the Belarusian part of the CEZ. In 2016, the Chornobyl Radiation and Ecological Biosphere Reserve was established in Ukraine. These scientific and conservation institutions carry out research work and monitoring of wildlife in the territory of the Exclusion Zone.

In the immediate aftermath of the accident, local wildlife was exposed to extremely high levels of radiation. This had a devastating effect on vegetation and wildlife, especially in the immediate vicinity of the destroyed reactor. Today, however, most of the CEZ has nothing in common with a nuclear desert. In fact, under conditions of almost total absence of anthropogenic pressure, wilderness has begun to reclaim areas that were once densely populated and intensively used for agricultural purposes. For instance, censuses have shown that red deer, roe deer, elk, and wild boar are increasing in the abandoned areas. The introduced Przewalski’s horses and European bison formed stable and growing populations. According to the same research, the number of grey wolves in the CEZ is several times higher than in some uncontaminated nature reserves in Belarus. Other research supported by our project showed that the Eurasian lynx density in the CEZ is significantly higher than in some other protected areas. Remarkably, camera traps deployed in the Chornobyl Radiation and Ecological Biosphere Reserve have detected the presence of brown bears in the Exclusion Zone.

In the 20th century, the once swampy areas of today’s CEZ were heavily drained for agricultural purposes. Soon after the accident, numerous drainage canals in the Belarusian part of the CEZ were blocked to prevent wildfires and the discharge of contaminated water. And the landscape started to change: mires and forests are gradually replacing farmland. Subsequently, the species’ composition has changed, too. For example, the abundance of bird species dependent on humans or transformed landscapes decreased, while the globally endangered Greater spotted eagle is recolonising the CEZ. These predators, which depend on intact wetlands and are extremely sensitive to human disturbance during nesting, seem to have found ideal habitat here.

At the same time, some scientists are warning their colleagues against undue optimism and calling for other aspects of the problem to be considered. Some studies show negative long-term effects of low-level radiation on several generations of mammals. Others point out that some bird species have shown a tendency towards more frequent genetic mutations and reproductive difficulties in areas with relatively high levels of contamination. The abundance of various species – from soil invertebrates to mammals – is reported to have decreased in such areas. At the same time, opponents insist that radiation as such is not the only possible explanation for the observed adverse effects. The heated debate continues, but it’s clear that many aspects of post-Chornobyl biology remain to be studied.

The Russian military invasion of Ukraine in 2022 seriously disrupted research work in the CEZ. At the very beginning of the war, Russian troops occupied the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant and the adjacent areas of the Chornobyl Radiation and Ecological Biosphere Reserve. As a result, the reserve’s property and equipment were damaged or destroyed, and the area is still mined. This makes any field work extremely difficult and dangerous. And yet, despite all the difficulties, activities in the CEZ haven’t stopped completely. The staff continue to carry out radiological and wildlife monitoring and are working to prevent the spread of radionuclides from the contaminated areas.

One of the most serious problems in the Ukrainian part of the CEZ at the moment is wildfires. Unlike the Belarusian part of the zone, the Ukrainian one has been heavily drained to prevent the spread of contamination by water flow. However, the result has been detrimental: frequent fires now cause severe air pollution and radioactive emissions. In 2020, 5% of the area was affected by flames. Fortunately, firefighters were able to prevent the radioactive waste dump from catching fire that year. Scientists emphasise that restoration of drained and disturbed wetlands is the most efficient nature-based solution to the problem of landscape fires. Large-scale wetland restoration in the Ukrainian CEZ is currently impossible. However, a site in this part of Polesia is among five areas selected for rewetting as part of our project. We hope to equip the reserve’s staff with the skills and knowledge needed to expand restoration in the future.

The Chornobyl Exclusion Zone is a unique area in Polesia, where the unintentional ecological experiment has been going on for almost 40 years and is unlikely to end in the foreseeable future. Paid for with the lives and health of thousands of people, numerous personal tragedies and harmful ecological consequences, it gives us a rare opportunity to gain valuable knowledge and reflect on the role of humankind in the environment of our planet.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

Numbers matter: the densities of lynx populations in Polesia have been calculated for the first time

Numbers matter: the densities of lynx populations in Polesia have been calculated for the first time

The Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) is one of the key large carnivores in Polesia. Despite its high conservation importance, the Polesian populations of this species are very poorly studied. The unprecedented camera trapping survey carried out in 2020-2021, and supported by our project provided the first scientifically based assessment of the Eurasian lynx population density in Polesia's protected areas. This paves the way for further research into the status of the species in the region, as well as its effective conservation locally and across its range.

The Eurasian lynx is widely distributed across the continent, with relatively stable numbers and legal protection in many countries, but is still threatened by anthropogenic factors such as habitat fragmentation and illegal hunting. It is therefore necessary to assess the status of populations across the species’ range in order to coordinate conservation efforts and make them effective. Currently, the Eurasian lynx is being studied unevenly across its range. In many European countries, lynx populations are systematically monitored using widely recognised scientific methods. At the same time, data on lynx abundance and density are scarce in Ukraine and Belarus, despite the fact that the species is protected in these countries.

In both Belarus and Ukraine, lynx are counted by hunting communities and forestry departments, but these efforts are neither systematic nor scientifically based. Double counting is common, making the estimates inaccurate. As well as provoking conflict between stakeholders, an inaccurate assessment of the status of a species can lead to inappropriate action. For example, the hunting community in Belarus is lobbying for a binary status for the lynx, which would keep the species in the Red Data Book but allow it to be hunted. They argue that lynx numbers are increasing significantly. However, there is no scientific evidence to this statement.

Correctly estimating the number and density of Eurasian lynx in is crucial, as the local populations are of high conservation importance, linking the species’ populations in Central and Eastern Europe. A large-scale survey supported by our project is the first attempt to fill this information gap.

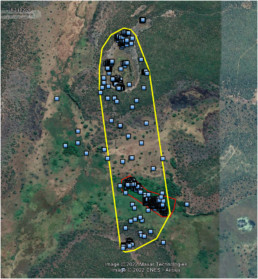

From October 2020 to March 2021, an extensive camera trapping survey for lynx was carried out in three biodiversity hotspots in Ukraine and Belarus – Skolivski Beskydy National Park in Ukrainian Carpathians, the Ukrainian Chornobyl Exclusion Zone (UCEZ). and three adjacent protected areas and a state forest in Belarusian Pripyat Polesia (BPP). The last two mentioned areas are located in Polesia. 65 and 50 trapping sites were surveyed in the UCEZ and BPP respectively.

To determine population densities, Palmero et al. (2023) used the well-established spatial capture-recapture (SCR) method, which incorporates fine-scale spatial information associated with individual detections into population models. They found that the Eurasian lynx densities within the study areas varied from 0.45 to 1.54 individuals/100 km2, with the highest numbers in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone. This is similar to other study areas in Europe where the same indices were determined using the same methods. The researchers suggest that the higher density of lynx in the CEZ is due to its large area, abundance of prey and low anthropogenic pressure, while in the Belarusian Pripyat Polesia the population faces lower habitat quality and prey abundance, as well as a higher risk of mortality due to poaching.

The work carried out and the results obtained are groundbreaking for both Belarus and Ukraine, and serve as a basis for further research on local Eurasian lynx populations and their conservation. It is also an important contribution to understanding the status of the species at the European level. The authors of the study point out that the data obtained will be important for future assessments of the impact of threats on the populations studied. They also suggest that protected areas play an important role in the conservation of the Eurasian lynx. Although large carnivores easily move beyond the boundaries of nature reserves or national parks, these protected areas still serve as refugia for the animals.

The authors emphasise that consistent, science-based monitoring of the Eurasian lynx, using the same methods across the continent, is key to understanding the species’ status and planning effective conservation measures.

Palmero, S., Smith, A. F., Kudrenko, S., Gahbauer, M., Dachs, D., Weingarth-Dachs, K., Kashpei, I., Shamovich, D., Vyshnevskiy, D., Borsuk, O., Korepanova, K., Bashta, A.-T., Zhuravchak, R., Fenchuk, V., & Heurich, M.(2023). Shining a light on elusive lynx: Density estimation of three Eurasian lynx populations in Ukraine and Belarus. Ecology and Evolution, 13, e10688. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.10688

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

The year 2023: conservation wins and new plans for Polesia’s wilderness

The year 2023: conservation wins and new plans for Polesia’s wilderness

2023 was probably one of the most challenging years for nature conservation in Polesia. The ongoing war has forced us to put many activities on hold and revise our plans, and many natural areas in the project region are simply inaccessible. And yet, looking back, we see that our efforts are not in vain - they are bearing fruit, albeit sometimes only after a while. We are learning more about Polesia's nature, taking steps to better protect it, and have big plans for the new year!

Wetland restoration in Ukraine: getting closer to becoming a reality!

The year 2023 started with really good news: we started preparation for restoration of several disturbed wetlands in the Ukrainian part of Polesia.

Though Ukraine is still at war, we, jointly with our partners, organised a meeting on the ground this year with a series of stakeholder discussions and field visits. Wetland restoration is now high on the agenda in Ukraine, with more and more people recognising the importance of ‘healthy’ and fully functioning wetlands. Conservationists point to their major impact on climate change mitigation and biodiversity conservation, while local communities witness the consequences of wetland drainage, which was widespread in Ukraine in the 20th century: lack of drinking water, land degradation, increasing frequency of droughts and growing threat of wildfires. During the war, many people recall another role of wetlands not only once proven in the course of history: barely passable mires serve as a natural defence line and a barrier against possible military invasion.

Seizing the opportunity, experts from the Michael Succow Foundation assessed the feasibility of restoring a number of wetlands and shortlisted five sites in Ukrainian Polesia for restoration.

The sites are located in different administrative regions of the country, and it is expected that our work will result not only in the restoration of 20,000 hectares of degraded wetlands, but also in the creation of groups of experts in each region, equipped with restoration knowledge and experience, who will be able to expand this process in the future.

Better protection for areas, biotopes and species

While we are focusing on landscape restoration in Ukraine, our efforts on putting new wilderness areas under protection in Belarus undertaken in 2020-2021 bore fruit. Here, we still find vast areas of well-preserved and functioning natural landscapes that are of high conservation value, but they still don’t enjoy full-scale protection and are mainly threatened by anthropogenic factors. The first thing they need is a legal protection status that will ensure the implementation of systematic and science-based conservation measures.

In 2023, a new nature reserve, Lva Floodplain, was designated in the Belarusian part of Polesia. This is the result of several years of the systematic work: initially, the designation was initially lobbied by our project in 2020-2021. The total area of the nature reserve amounts to 2,400 hectares. It is a part of the national ecological network, a prospective Ramsar site and a potential UNESCO biosphere reserve. The new nature reserve occupies a part of a vast forest and mire complex in the Lva River floodplain, which is an important ecological corridor and a key area for rare bird species as the Greater Spotted Eagle (Clanga clanga) and the Hen Harrier (Circus cyaneus). In total, field surveys proved the presence of 588 plant species and 181 species of terrestrial vertebrates, including 27 bird species and 8 mammal species listed in the Red Data Book of Belarus, in the Lva Floodplain. Importantly, the new protected area borders the Almany Mires Nature Reserve, which enhances the ecological connectivity.

Smaller natural areas that need protection can be represented by separate habitat sites of rare species or by valuable biotopes that, being once destroyed, can never be fully restored back to their natural state. This year, 5,000 hectares of rare and typical biotopes as well as habitat sites of rare species were taken under legal protection in Belarusian Polesia. 13 additional nesting sites of the globally vulnerable Greater Spotted Eagle (Clanga clanga) are now protected. The field surveys were carried out, areas identified as being in need of protection and the relevant applications submitted to the state bodies back in 2021 as part of our project. The documents were finally adopted in 2023 by the relevant authorities.

Science: Advocating for more protected areas and wetland restoration

Research helps us to better understand the processes taking place in the Polesian landscape, to identify threats to its nature and to find the most appropriate approaches and solutions. In 2023, a number of papers were published based on research and field surveys carried out in Polesia in previous years.

Landscape fires are a pressing issue for Polesia: vast drained areas became prone to fires, the most dangerous of which occur in peatlands. Fires threaten the safety, health and lives of people and do damage to the economy. A lot of resources are spent for fighting fires during hot and dry periods. The problem is likely to get worse as the climate changes. The authors of a recent study from our partner organisation the British Trust for Ornithology have mapped and analysed large fires that occurred in Polesia over a 19-year period. For the first time, researchers have determined the patterns, environmental and human drivers of fires in Polesia’s ecosystems. Unfortunately, fires disproportionally affect Polesia’s protected, internationally important peatlands and floodplain meadows, and the most extreme fires threaten primeval deciduous forests. The authors of the study are convinced that there is a cost-effective, nature-based solution to the problem – restoration of the drained wetlands that could set natural barriers to large devastating fires.

Using widely available satellite data and a cloud-based software, the authors of the study elaborated a replicable methodology that can be applied anywhere in the world, positively impacting landscape restoration and effectiveness of fire protection measures.

Another recent publication focuses on the Polesian population of the Grey Wolf (Canis lupus). The population is still understudied, although it is of great conservation importance as a link between large populations of the species in Poland and the Baltic States on the one hand, and the Russian Federation on the other. The authors analysed the impact of anthropogenic factors on the habitat suitability of wolves in Polesia. Correlating the confirmed facts of the presence of the species with the characteristics of the landscape, they concluded that wolves avoid areas with a prevalence of cropland, a high index of artificial light at night and a high density of roads. This means that the anthropogenic impact on the distribution of the grey wolf is high. The authors of the study conclude: Although 26% of Polesia’s territory is suitable for the species, not all of these areas are occupied by wolves. Some high quality areas are isolated from each other and it is very important to prevent their further fragmentation. On the contrary, the creation of new protected areas is important to ensure stable connectivity between core protected areas for wolf conservation.

The Polesian population of the Eurasian Lynx (Lynx lynx), like that of the Grey Wolf, is still understudied. The lynx is a key carnivore species for the whole of Europe and has a major ecological impact on ecosystems. Lynx populations in Belarus and Ukraine are linked to populations in other parts of Central Europe, so understanding their status is important for developing Europe-wide measures to protect the species.

The unprecedented camera trapping survey carried out in 2020-2021 in the protected areas of Polesia, including the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone in Ukraine and the nature reserves of Pripyat-Polesia (central part) in Belarus, became the basis for systematic, science-based research on the species in the region. The work resulted in the most valuable and comparable lynx density estimates for Ukraine and Belarus to date. The authors of the study point out that the species is threatened by poaching and habitat fragmentation caused by anthropogenic factors. Therefore, protected areas play a significant role as refugia for lynx. However, more research is needed to understand other aspects of the species’ status, such as the genetic diversity of the population or the full range of ecological and anthropogenic factors affecting the species in the region.

Everything we have achieved this year is, on the one hand, a continuation of the great systematic work started several years ago. On the other hand, it paves the way for a deeper understanding of the nature of Polesia and makes practical steps for its conservation and restoration more reasonable and targeted. We go into the new year not carelessly, but with faith in our work for the sake of the Polesia’s nature and people.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

Restoration feasible: five drained wetlands in Ukrainian Polesia are to be rewetted

Restoration feasible: five drained wetlands in Ukrainian Polesia are to be rewetted

Among the highlights of our project activities this year, the preparatory work for wetland restoration in Ukraine stands out. Jointly with our partners, we have selected five sites in the Ukrainian part of Polesia for further restoration. All of them are wetlands disturbed by drainage, and the planned actions will involve changing the hydrological regimes of these sites.

Though Ukraine is currently at war, environmental issues are high on the agenda. “Healthy” wetlands of Ukrainian Polesia are vital for the whole of Ukraine. Their water resources feed the country’s major rivers, such as the Dnieper providing drinking water for millions of people. And the results of intensive drainage of this area in the mid-20th century are disastrous. While experts are sounding the alarm about the loss of biodiversity, rising greenhouse gas emissions and temperatures, local people are witnessing the degradation and often abandonment of land, increasing frequency of droughts, lack of clean drinking water and critical air pollution from particles emitted during wildfires. This is why more and more people are speaking out in favor of wetland restoration.

Seizing the moment, our partners at the Michael Succow Foundation carried out a feasibility assessment of potential restoration sites in the Ukrainian part of Polesia. They considered a wide range of aspects, including the spatial, ecological and hydrological characteristics of the sites. Thus, attention was paid to sites’ location and area, peatland type, presence or absence of drainage systems and their current state and size, maximum land surface temperatures and frequency of landscape fires, the legal status of the areas and stakeholder analysis, expected complexity and costs of restoration. As a result, the experts identified five sites (totalling 20,000 ha) with the best prospects for successful restoration and agreed further action with stakeholders.

All of the selected sites have drainage canal systems on their territory. However, the sites differ significantly in terms of their degree of disturbance, spatial and ecological characteristics and drainage system features. Therefore, each site requires a special approach and an individual set of measures to improve its condition.

The Cheremske Bog is located in the Volyn and Rivne regions. Although somewhat disturbed by an attempt to drain it in the early 20th century, it is now generally in good functional condition and only needs some support. Our aim is to prevent any further drainage of the area to make it more resilient to changing climate conditions.

The Somyne Swamps and Syra Pogonia Bog are located close to each other in the Rivne Oblast. The Somyne Swamps have a very special page in its history: in the 1920-1930s, when the state border between Poland and the Soviet Union crossed the present-day territories of Ukraine and Belarus, a very peculiar defense line was built on the Polish side. Apart from fortifications and bunkers, it included Polesian rivers and mires as natural barriers. The Somyne Swamps were a part of this Polesian defense line. Nowadays it is in need of restoration, having been disturbed by drainage and amber mining.

The Syra Pogonia Bog is adjacent to the Almany Mires peatland compex located northwards, across the Ukrainian-Belarusian border. Together they form the largest complex of raised, transitional mires and fens in Europe. Syra Pogonia has the characteristics of northern (taiga) wetlands, which are unique for Ukraine and Central Europe. The site is rich in biodiversity and serves as an important breeding site for wetland birds, including the globally threatened Greater Spotted Eagle (Clanga clanga). The peatland has been severely affected by drainage and suffers from frequent wildfires.

Not only the construction of drainage canals has influenced the hydrological regime of Polesia in the past. Many rivers have also been altered. As a result of the deepening and channelling of the Zholobnytsia River and the construction of a network of drainage canals, the river’s floodplain was reclaimed for agriculture in the mid-20th century. Today, the land is no longer suitable for agriculture and the drainage system has been abandoned. Preliminary analysis showed that in order to ensure successful restoration of the hydrological regime in this area, it might be necessary not only to block up the canals, but also to reverse the river bed alteration.

Another distinctive site selected for restoration in Polesia is the Uzh river floodplain, located in the Kyiv region, in the southern part of the Chornobyl Radiation-Ecological Biosphere Reserve. Before and after the nuclear accident, the area of what is now the reserve was heavily drained to prevent the spread of contamination. Now the area suffers from devastating fires: in 2020, the flames affected almost 5% of the area and were one step away from the “red zone” where radioactive waste is stored. Those fires caused extreme air pollution in Kyiv. Restoring the wetlands in the areas surrounding the Chornobyl nuclear power plant is therefore of paramount importance. However, following the start of the full Russian invasion, a significant part of these areas are still mined. This is the main obstacle to large-scale wetland restoration in the Chornobyl zone. Nevertheless, it has been decided to start the work in a safe place, so that it can be continued as soon as it is safe to do so.

Importantly, the selected territories are located in four administrative regions of Ukraine comprising the territories of Polesia – Volyn, Rivne, Zhytomyr and Kyiv. Thus, after restoration of the proposed sites, each region will have a team of experts with practical experience in restoration: site selection, stakeholder involvement, administrative procedures, preparation, monitoring, construction works and evaluation of the results achieved. They will be able to scale up wetland restoration activities in their regions, each of which has quite large areas in need of rewetting.

Olga Denyshchyk, scientific project coordinator at the Michael Succow Foundation:

“We plan to carry out the restoration work as openly as possible to show how rewetting works and what benefits it brings. Maybe we will develop an algorithm for such works, because many environmental organisations are interested in this topic, but unfortunately there is little experience in Ukraine. We want to set a positive example for professionals and residents of Ukraine – this will allow restoration work to be carried out on a much larger scale in the future.”

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

Gone forever? How Polesia lost and regained its rare species

Gone forever? How Polesia lost and regained its rare species

According to scientific estimates, around 1 million species of flora and fauna on Earth are currently threatened with extinction. We are witnessing a major biodiversity crisis that is, however, not the first one in the history of our planet. What makes it different is that this time, it is almost entirely due to human activity. Will rare species disappear forever, or do they still have a chance to move away from the danger line? It is hard to say for sure. But some local cases from Polesia give cause for cautious optimism.

A terrible disaster as a chance for wildlife

The accident at the Chornobyl nuclear power plant in 1986 is sometimes described as the worst man-made disaster in history. Its impact on people’s health and well-being, the economy and the environment is still enormous. A large area around the epicentre of the disaster, once densely populated and used for agriculture, was abandoned by people because of the contamination. Wildlife immediately seized the opportunity and began to reclaim the now uninhabited territory.

One of the rare species to benefit from this situation is the Greater Spotted Eagle (Clanga clanga) – a globally endangered bird that was locally extinct in what is now known as the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone. These birds depend on intact wetlands for foraging and breeding and suffer from habitat degradation and human disturbance. After the unguided rewilding of the exclusion zone had begun and former croplands had given way to mires and forests, the Greater Spotted Eagles started recolonizing this territory which is now the only place on Earth where the population of this rare eagle is growing.

The Chornobyl Exclusion Zone is home to one more globally endangered species – the Przewalski’s horse (Equus przewalskii). Its population declined in the 1940-1950s and was considered extinct in the wild in the 1960s – only captive individuals in zoos of various countries were saved. However, as a result of successful captive breeding efforts, the number of Przewalski’s horses has increased and some were released into the wild. In 1998, 31 animals were introduced to the exclusion zone in Polesia. Within 20 years, the local population had grown to 150 animals. Indicators of genetic diversity show that this population of the Przewalski’s horse has good prospects for further growth.

Extinct or lying low?

In the last century, the European mink (Mustela lutreola) was widespread in Polesia and in Europe as a whole, but now the species is as rare as hen’s teeth. This is because a few thousand American minks (Neogale vison) were brought to Europe in the 1930s for the fur trade. They were originally intended to be bred on farms. Later, however, some of the ‘aliens’ got into the wild. The native species could not compete with the more aggressive and strong invasive animals. The European mink was driven out of most of its historic range and became a critically endangered species. It has not been seen in Polesia for more than 20 years, and some experts believe it is extinct in the area.

In 2021, field biologists from our project set out to rediscover the European mink in Polesia. They installed 25 camera traps along rivers and drainage canals in remote areas of the Almany Mires Nature Reserve. Unfortunately, no picture of the European mink was captured. However, this does not necessarily mean that the species has disappeared from the region: the next story shows what surprises are possible when it comes to biodiversity.

Polesia is home to at least 12 species of bats, including a real rarity – the Greater Noctule (Nyctalus lasiopterus), the largest bat in Europe. This species is rare, its range is fragmented and the smallest among the European bats. The Greater Noctule was thought to be locally extinct in Polesia. Once a male bat was shot in 1930: this was the last sighting of the species in the region until 2009, when a young male was captured by a group of researchers in the Ukrainian part of the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone. In 2015, two lactating female Greater Noctules were entrapped during a bat census in Belarusian Polesia. This proved that the rare bats were breeding in the region! In 2017, new observations of the Greater Noctule were made, and later, they were also identified in the course of acoustic monitoring as part of our project.

The Greater Noctule is an indicator species for the natural state of the old-growth forests. Its decline in Europe is caused by lack of suitable habitat – old-growth forests with a large number of hollow trees in a small area to ensure the successful functioning of a bat colony. In more than half of the cases, the Greater Noctule prefers to live in dead trees. This demonstrates the crucial importance of deadwood preservation for biodiversity conservation.

The cases described show that there is often a chance to reverse worrying trends and bring rare species back from the brink of extinction. And let’s use the memory of species that we will never see again in the wild as an incentive to do our best to ensure that their number grows as slowly as possible.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

Anthropogenic factors limit suitable habitat for wolves in Polesia

Anthropogenic factors limit suitable habitat for wolves in Polesia: new study

The conservation of the Grey wolf (Canis lupus) in Europe has been quite successful, with numbers increasing and the grey carnivore reappearing in many places where it was once completely extirpated. Meanwhile, the Polesian population of wolves is poorly understood, despite its high conservation importance. A new study supported by our project is one of the first attempts to fill this gap and analyse the habitat suitability of wolves in Polesia, taking into account both environmental and, more importantly, anthropogenic factors.

According to official estimates, wolves occur throughout Polesia and their numbers are the highest among the large carnivores of the region. However, the species is only regularly recorded in some protected areas, and overall, the wolves’ densities, distribution and movements in this large region have not yet been systematically studied. Meanwhile, this information is very important for understanding the status of the wolf in Europe as a whole: the Polesian population of the species is of high conservation importance as a link between the wolf population in Russia and those in Poland and the Baltic countries.

The Grey wolf has never disappeared from Polesia. Up to the middle of the 20th century, it used to be widely spread in both Belarus and Ukraine. After the Second World War, however, wolves were regarded as a vermin species threatening the economy and human safety. This entailed systematic overhunting, which, alongside with habitat fragmentation and degradation caused by anthropogenic impact, led to the decline of the wolf population. Still hunted year-round in most of Polesia (in both Ukraine and Belarus), wolves have not disappeared, however, but often find refuge in dense forests and impassable mires.

The authors of the study aimed to assess the influence of anthropogenic factors on habitat suitability for wolves and to quantify the extent of their suitable habitat in Polesia. They compiled the wolf presence data collected between 2014 and 2021 from several sources: telemetry data, remote camera-trapping studies, scat samples confirmed by genetic analysis, and geo-referenced wolf records (i.e. photos, remote camera records, and other confirmed observations). To predict suitable habitat, they selected a set of key variables characterizing the landscape, including three related to land cover in the study area (land cover type, tree cover, and Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)). Among the variables that reflect the anthropogenic impact, artificial light at night (ALAN), the proportion of cropland, and road density were selected as the most relevant. The wolf presence data were matched to the characteristics of the landscape and then analysed in a 1 km resolution grid.

Data analysis showed that cells with wolf presence differed significantly from those without the species. The animals prefer areas with low ALAN values. The researchers point out that this variable is a better indicator of human presence than census data or the population density index. The proportion of cropland and the density of roads were also lower in the cells with wolves. At the same time, tree cover percentage and NDVI values positively correlated with recorded wolf presence. Additionally, wolf observations were more frequent in cells with forests and wetlands as the dominant habitat type. This could be explained by the abundance of prey and low human disturbance. Alongside similar European studies, the new research confirmed that wolves avoid areas with permanent human presence.

Overall, the proposed model showed that 26% of the territory of Polesia (approximately 42,000 km2) is suitable habitat for the Grey wolf, of which more than 14,300 km2 is highly suitable. The rest of the landscape has low or very low suitability values. At the same time, even suitable habitats are only partially occupied by wolves.

The study showed that core protected areas for wolf conservation in the Polesia region are the Białowieża Forest, the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone with the neighbouring Drevlyanskyi Strict Nature Reserve and the central part of Polesia (Almany Mires Nature Reserve, the Pripyatskyi National Park, the Mid-Pripyat Nature Reserve and the Rivnenskyi Strict Nature Reserve). These protected areas have between 37% and 77% suitable habitat within their boundaries. High-quality unprotected areas suitable for wolves have also been identified. Some of these are isolated but still accessible for wolves.

The authors of the study explain that some high-quality areas are not well connected with other sites. Therefore it is very important to prevent their further fragmentation. The study made it possible to identify the areas that could be taken under protection in order to ensure better connectivity between core protected areas that are crucial for wolf conservation. Thus, this research lays the foundation for the further expansion of the protected area networks as well as for effective, long-term wolf monitoring and management programmes in both Belarus and Ukraine. This variety of measures has the potential to strengthen grey wolf conservation in the region.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

Between Polesia and Zambia: a Polesian eagle chooses a very unusual wintering site in Africa

Between Polesia and Zambia: a Polesian eagle chooses a very unusual wintering site in Africa

Greater Spotted Eagles from Polesia are about to start their autumn migration southwards. Their wintering sites are scattered across Europe, Asia and Africa: these birds spend the cold season in the Balkan Peninsula, Israel, South Sudan, Zambia, and even South Africa. Thanks to GPS-tracking, we not only have a chance to discover migration patterns that are important for the conservation of this rare species, but also learn many curious details that make even experienced scientists surprised. One of these was recently discovered and described by ornithologist Valery Dombrovski.

Liada is a female eagle nesting in the Mid-Pripyat Nature Reserve in Polesia. She spends every winter in Zambia, in a tiny area of only 3 square kilometers. This is too small even for a Greater Spotted Eagle, but Liada is a hybrid between Greater and Lesser Spotted Eagles. Typically, wintering Lesser Spotted Eagles have several feeding sites located at a significant distance from each other. Because of this, vast wintering areas of tens of thousands of square kilometers are formed.

Wintering grounds of Greater Spotted Eagles are much smaller; however, they usually also reach dozens of square kilometers. It means that Liada is an exception to the general rule. Every day, she flies only a couple of kilometers from one part of the forest to another. How can she survive in such non-typical conditions? I had to dig deep into the internet to figure it out. Fortunately, this part of Zambia is well known to scientists and naturalists. The area belongs to the Kasanka National Park, famous for its biodiversity. It is home to various species of bushbucks, blue monkeys, and about 400 bird species. And then I found out that one of the most famous natural “shows” occurs in Kasanka annually, and it attracts numerous tourists from around the world.

From the middle of October to late December, over 10 million of Eidolon Fruit Bats (Eidolon helvum) congregate in Kasanka. All of them arrive in the wetland forest with a total area of about 2 ha, thus forming the highest density of mammals in the world. Eidolon Fruit Bats are quite big – their weight can reach 350 g. The enormous number of resting bats causes tree branches to bend and even break.

No wonder that the congregation of bats attracts numerous predators. The forest turns into a feeding ground for birds of prey. In addition, there are crocodiles, snakes and leguans waiting for some unfortunate bat to come tumbling down.

And what about our Liada? Is she part of this natural spectacle? Yes, she is! She arrives in Zambia in late October, simultaneously with the bats, and then visits the bat forest almost every day. Obviously, Liada like many local predators, feeds on this mysterious natural phenomenon – the mass congregation of Eidolon Fruit Bats in the same place.

Isn’t this impressive? Liada nests in Polesia, looks and behaves just like dozens of other Greater Spotted Eagles, but at the same time she is the link that connects us to an outstanding natural phenomenon in a different part of the globe. What secrets do other ‘ordinary’ Greater Spotted Eagles hold? We can only guess and hope for new, unexpected discoveries.

The top image features Greater Spotted Eagle Liada in flight. The photo is taken by Brett Lewis in Kasanka National Park, Zambia.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).