Chornobyl on fire: the growing problem of wildfires in the Exclusion Zone

Chornobyl on fire: the growing problem of wildfires in the exclusion zone

Landscape fires are a natural process in ecosystems. But a combination of anthropogenic and climatic factors can turn them into an acute problem. Experts predict that temperate regions are likely to be at risk of increasing frequency of large and devastating fires due to climate change. The Chornobyl Exclusion Zone (CEZ) is one of the areas where the problem of landscape fires is already acute, exacerbated by the heavy contamination of the area. Therefore, fighting and - even more importantly - preventing wildfires are among the priority tasks in the management of this extremely significant territory.

The Chornobyl Exclusion Zone that emerged after the accident at the nuclear power plant in 1986 is shared between Ukraine and Belarus being a part of Polesia. It is considered one of the most heavily contaminated by radionuclides areas in the world. In both countries the Exclusion Zone is protected, controlled and studied. In 1988, the Polesie State Radioecological Reserve was founded in the Belarusian part of the CEZ. In 2016, the Chornobyl Radiation and Ecological Biosphere Reserve was established in Ukraine. Scientists and conservationists carry out research and monitoring of the radiation contamination, landscape dynamics and wildlife in the area of the Exclusion Zone.

The main consequence of the Chornobyl accident is the severe radioactive contamination of a large area. It’s extremely important to take measures to prevent the spread of radioactive substances that have accumulated in the environment. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Belarus and Ukraine have taken such measures independently and in different ways.

In 1992-1993, many of the drainage channels in the Belarusian part of the exclusion zone were blocked. This measure was planned to reduce the spread of radioactive sediment from the Pripyat River basin downstream, but a significant portion of the soluble strontium had already been carried to the Pripyat River in the years after the accident. Over time, this also led to increased water retention in the canals, contributing to the rewetting of certain areas and the recovery of wetland ecosystems.

In the Ukrainian part of the CEZ, canals in the most contaminated areas were also blocked in 1986 and the following years, as part of a comprehensive plan to protect water resources from radiation contamination. At the same time, a strategy was chosen to maintain minimal flooding of the catchment area to reduce the water migration of strontium-90 and other radionuclides. These almost opposite tasks required such a scenario for managing the former drainage systems to retain water during periods of high risk of landscape fires, but to prevent prolonged flooding of the territory.

Experts note that the total length of drainage canals in the Ukrainian part of the Chornobyl Zone is four times greater than the length of the small rivers of this territory. Since the accident, the drainage infrastructure has gradually deteriorated and the canals are now overgrown with bushes and grass. Some natural restoration of the wetlands is taking place. However, the scale of these positive processes is insignificant and the drainage systems continue to have a draining effect on the surrounding area.

Another factor exacerbating the problem of fires in the Chornobyl Zone is climate change. Periods of hot, dry weather have become more frequent and longer in recent years. Instead of prolonged rainfall, there are more short-term rains that evaporate quickly, leaving little time for rivers and aquifers to recharge. Winters with little or no snow are becoming increasingly common in Polesia. This means that the soil remains unsaturated with moisture until spring. If we speak about peat soils typical for region, the risk of large fires is very high here: dry peat burns easily, is difficult to extinguish and retains the smoldering nests for a very long time, which can be activated under favorable conditions.

Human factor: the cost of one thoughtless act

According to the research conducted as part of our project, two of he ten largest landscape fires in Polesia between 2001 and 2019 occurred in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone – one in the Belarusian part and one in the Ukrainian part. Fire statistics in the two countries can be unreliable, but overall the number of fires occurring on the Ukrainian side is several times higher than on the Belarusian side. Specialists insist that the human factor plays a key role here.

The human presence in the Ukrainian part of the CEZ is quite significant. Economic activity is limited here, except for the rather intensive activity of maintaining the nuclear power plant and radioactive waste storage facilities, as well as related infrastructure (roads, power lines, forestry, etc.). Before the Russian military invasion, tourism was highly developed here. Some people enter the zone illegally, there are squatters who return to their homes abandoned in the course of evacuation. The activities of local people whose farms border the reserve also play a role. They still burn dry vegetation in spring and after harvest – the times when most forest fires start on agricultural land and then spread uncontrollably to natural areas.

In recent years, there have been worrying reports of fires in the contaminated areas. A case in point is what happened in the spring of 2020. In early April, a fire broke out in the area adjacent to the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone and began to spread through the protected area. Investigations later revealed that it was most likely caused by the careless actions of a local resident. In dry and windy conditions, the fire spread rapidly. Embers formed in the dry peat bogs and ignited again when the wind picked up. The fire approached the nuclear power plant and the nuclear waste facilities. The flames also reached the so-called “Red Forest” – the woodland area around the plant which was exposed to the highest radiation doses during the 1986 accident and is still one of the most contaminated parts of the Chornobyl Zone. The total area affected by the fires reached more than 67,000 hectares. Hundreds of firefighters and a wide range of equipment, including aircraft, were used to extinguish the flames, but it took more than a month to bring the fires under control. Situation deteriorated after the Russian military invasion. In addition to natural conditions and human activities, unexploded ordnance contamination and a lack of firefighting equipment exacerbated the problem, reducing firefighting capacity and slowing fire suppression. In recent years big wildfires can be expected due to warfare consequences.

Radiation spreading: invisible danger

In the case of fires in the Chornobyl Zone, there are many concerns about the possible spread of radioactive substances by air currents along with the products of combustion. Specialists claim that the burning of the ground cover itself does not lead to a dangerous increase in background radiation. However, it increases radionuclide concentration in air and leads to migration with smoke.

Scientists at the Norwegian Institute for Air Research have studied the effects of forest fires on the atmosphere in the Chornobyl Zone in Ukraine and Belarus. They point out that the increasing amount of dead trees and litter can provide fuel for wildafires, which pose a high risk of radioactivity redistribution in future years. According to their modeling, intense fires in 2002, 2008 and 2010 caused caesium-137 to move southwards; the cumulative amount of caesium-137 redeposited over Europe could be 8% of the amount deposited after the Chornobyl disaster in 1986. A large amount of dangerous, long-lived and refractory radionuclides are still present in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone. Scientists predict a high risk of radionuclide redistribution in the future due to the expansion of the burnable area associated with climate change.

A field study conducted jointly by Ukrainian and Japanese scientists has found that the rate of radionuclide leaching and weathering after fires temporary increases by a factor of 30 compared to the rate before the fire.

Fires and wildlife

The Chornobyl Zone is often cited as a benchmark example of unguided rewilding. With very little human influence in recent decades, wildlife has regained its territory. The proportion of forests and mires has increased significantly, and populations of many wild animals, including ungulates, predators such as lynx and wolf, as well as rare birds, have grown. Where intensive agriculture was once practiced, plants listed in the Red Book now grow. But this progress can easily be undone by flames. Large fires cause great damage to natural values. They destroy forests, which regrow slowly. Small and sedentary animals die because they cannot escape quickly from the oncoming fire and smoke. Large animals may escape, but when they return they find their habitat is no longer suitable. Spring fires, which coincide with the nesting season of birds, disrupt their breeding cycles.

Experience in recent years has shown that during long periods of drought, with strong winds and a lack of moisture in the natural environment, forest fires become difficult to control. Fighting the fires and dealing with the aftermath requires significant resources and financial investment, and the negative consequences are multifaceted and severe. Obviously, it is important to build the capacity of fire–fighting services and to combat the irrational and dangerous behavior of local residents through both educational and administrative measures. In the long term, however, the most effective way may be to restore the water regime in areas where there is a problem of water scarcity. Let us not forget that many scientists predict that this problem will only get worse in the context of climate change.

One of the current priorities of our cooperation with the Chornobyl Radiation and Ecological Biosphere Reserve (Ukraine) is the rewetting of previously drained areas. Large-scale restoration of wetland ecosystems in this area is currently impossible. However, our role is to work with the reserve’s specialists from site selection through to practical implementation, so that they gain the experience and knowledge necessary to continue this vital work in the future.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

Bats’ cozy home: a rare bat rediscovered in the depth of Polesia is taken under legal protection

Bats’ cozy home: a rare bat rediscovered in the depth of Polesia is taken under legal protection

Polesia is home to a diversity of chiropters. Scientists have reliably determined that at least twelve bat species occur here. However, the nature and peculiarities of the local habitats suggest that their number may reach up to twenty. The most important discovery was the fact that the Greater Noctule (Nyctalus lasiopterus), the largest bat in Europe, thought to be extinct from the region, can still be found in remote corners of Polesia. Thanks to the efforts of our project in the years from 2019 to 2022 , the Greater Noctule is included in the new edition of the Red Book of Belarus with the highest protection status.

The vast natural areas of Polesia are still not fully explored. Perhaps no scientist can boast of having travelled through them backward and forward. However, the region’s old-growth forests, floodplains and hardly passable bogs remain a promising field for biodiversity research, as they still serve as refuges for rare species of flora and fauna whose habitats are shrinking under the pressure of anthropogenic change.

It is interesting and important to study the bat populations in Polesia. These animals are very sensitive to changes in ecosystems, so their presence can serve as an indicator of habitat quality and importance for maintaining biodiversity. New research methods, such as passive acoustic monitoring, make it possible to quickly obtain large data sets for study. To assess the importance of the region for rare species, including bats, and to identify the areas of high conservation importance, our project carried out the first acoustic monitoring study in Polesia. Specialists installed acoustic recorders in 500 locations across the area. These devices record nocturnal forest sounds which are then sampled and classified by a special software. When it comes to bats, recording their sounds is much easier than catching these nocturnal animals in nets or using camera traps.

Acoustic monitoring confirmed the presence of 12 bat species in the Polesia study sites. However, this does not exclude the possibility that other species of chiropters occur there as well. One of the most important results of the study was the confirmation of the presence of the Greater Noctule in the Belarusian part of Polesia. For more than 80 years, since the last sighting in 1930, this species was considered locally extinct. Shortly before our study, two lactating females were entrapped during the bat census in a rugged old-growth forest in the Stary Zhadzien Nature Reserve. Our acoustic monitoring study provided further confirmation of the presence of this rare species in Belarusian Polesia.

These data helped us to lobby in 2021 for the inclusion of the Greater Noctule in the Red Data Book of Belarus – the list of protected species is updated every ten years, and a new edition came into force this spring. The Greater Noctule received the highest protection status. It became the 9th protected bat species in Belarus, alongside the Pond Bat (Myotis dasycneme), the Northern Bat (Eptesicus nilssonii), the Grey Long-eared Bat (Plecotus austriacus), the Common Barbastelle (Barbastella barbastellus), the Natterer’s Bat (Myotis nattereri), the Lesser Noctule (Nyctalus leisleri), the Brandt’s Bat (Myotis brandti), and the Whiskered Bat (Myotis mystacinus).

According to national regulations, bat conservation measures in Belarus include the protection of permanent colonial hibernacula (hibernation places) and breeding settlements of these animals – trees, separate buildings, cellars or semi cellars, and old fortifications. Special protection rules in bat habitats include restrictions on the use of chemical pesticides, on economic activities that disturb bats during the hibernation period, as well as felling, removal, destruction, and damage to trees that host maternal colonies of bats, as well as some other measures.

The Greater Noctule is an indicator species for the natural state of the old-growth forests. The reason of the population’s decline in Europe is the shortage of suitable habitat – old-growth forests with a great number of old hollowed trees in a small area that ensure the successful functioning of a bat colony. Most often, the Greater Noctule chooses dead trees as habitats. Thus, deadwood preservation is crucial for the conservation of this endangered species, just like for a number of others.

Unfortunately, despite expert recognition of the important role old and dead trees play in ecosystems, these trees are still often felled. Only through an elevated status of protection of the natural area at the national and international level – with the conservation measures aimed not only at an individual species, but also at the ecosystem as a whole – we can ensure the survival of many rare and sensitive species, including bats.

For the first time in Polesia, automatic groundwater level measurement is used in wetland restoration

For the first time in Polesia, automatic groundwater level measurement is used in wetland restoration

The practical implementation of wetland restoration in the Rivnenskyi Strict Nature Reserve began with the start of hydrological monitoring in the Syra Pohonia Bog – one of our priority restoration sites. Our project’s experts carried out the field work together with the staff of the reserve.

Polesia is extremely rich in wetland ecosystems that are crucial for maintaining biodiversity, regulating water regimes, and mitigating climate change. However, in the past century, they have been subjected to drainage reclamation and other anthropogenic impacts, which has led to significant degradation of these ecosystems. Among the negative consequences of these processes are extreme fluctuations in water levels – from lasting droughts to destructive floods, growing carbon emissions and habitat transformation, burning of woodlands and peatlands, a decrease in surface waters quantity and quality during the low water period, and the development of wind erosion. As a result, habitats are undergoing radical transformation, and peatlands are no longer able to regulate water and carbon compounds. Restoration of hydrological regimes of the disturbed wetlands is the way to prevent further ecosystem degradation and loss.

Some time ago, we jointly with our partners selected a few sites with the best prospects of restoration in the Ukrainian Polesia. Two of them are located in the Rivnenskyi Strict Nature Reserve – they are the Syra Pohonia and Somyne mire complexes.

The Rivnenskyi Strict Nature Reserve, situated in the north of Ukraine, is the largest nature reserve in the continental part of the country, covering an area of 42 291.3 hectares. The area encompasses all the types of peatlands typical for Ukrainian Polesia that makes it unique. The reserve is also an important centre for the conservation of forest ecosystems dominated by pine forests. These forests and wetlands provide a habitat for numerous rare species of flora and fauna, underscoring the reserve’s pivotal role in safeguarding biodiversity in Ukrainian Polesia.

The Syra Pohonia Bog is adjacent to the Almany Mires Nature Reserve situated to the north, across the Ukrainian-Belarusian border. Together, these sites make up the largest complex of raised, transitional mires and fens in Europe. Syra Pohonia possesses the features of a northern wetland (taiga) that is unique to Ukraine and Central Europe. It is home to a variety of flora and fauna, including wetland bird species, such as the Greater Spotted Eagle which is at risk of extinction. Syra Pohonia has been badly affected by drainage and wildfires.

Works on restoration of the hydrological regime of the Syra Pohonia Bog involve specialists of our project, employees of the Rivne Strict Nature Reserve and the National University of Water and Environmental Engineering (in Rivne, Ukraine). The recently launched hydrological monitoring will track the ground water levels in the reserve’s disturbed mires and the outflow of water from the canals.

Automated methods of water regime control have been introduced to assess the effectiveness of the restoration work. The specialists are now able to process not only the data from the existing network of groundwater level observations within the reserve, but also the data periodically collected by means of modern equipment, such as an electromagnetic flow meter, automatic groundwater level and temperature data loggers (divers). With information about changes in water levels, the project team will be able to make informed decisions in the future to ensure that the restoration is carried out correctly and safely. The monitoring scheme is designed to assess the impact of the drainage channels and evaluate the effectiveness of the restoration measures.

According to experts’ estimates, now, Syra Pohonia loses about 2.5 million cubic meters of water per month during the spring flood due to the impact of drainage channels. Instead of accumulating water in the wet season and releasing it in the dry season, this water flows rapidly in the spring, causing flooding in the surrounding villages downstream. Instead, during the dry summer and fall months, there is a significant shortage of water and soil moisture, which leads to the spread of fires and has a negative impact on agriculture in the areas adjacent to the mires.

Serhiy Sorokin, regional project coordinator at the Frankfurt Zoological Society:

“We recognize the importance of restoring this bog not only for the environment, but also for the people who live near the reserve. By restoring the mires and carefully monitoring the hydrological conditions, we aim to improve the ecological balance, prevent excessive flooding, and create a more sustainable landscape for future generations”.

Fluctuations in the groundwater levels have a particularly strong impact on the local population, especially on residents of adjacent villages, who often suffer from seasonal flooding. By restoring marshland areas in the Syra Pohonia and Somyne massifs, the project initiators aim to raise and stabilize the water table within the reserve to reduce extreme water fluctuations outside of it, thereby reducing the risk of future flooding. This monitoring program will not only support the restoration process, but will also serve to inform communities of potential changes in water levels that could have a positive impact on their lives, such as increased water levels in wells or reduced risk of flooding of private households, agricultural land and local infrastructure.

The initiative aims to restore the hydrological regime of the Syra Pohonia and Somyne peatland complexes, as well as to predict the impact of restoration measures on the ecosystem. The restoration project is expected to last for 18 months, followed by continuous monitoring and research for at least the next 10 years.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

Polesia’s wetlands and people: depending on each other

Polesia’s wetlands and people: depending on each other

World Wetlands Day is celebrated around the world on the 2nd of February. This date is an opportunity to draw public attention to the global importance of different types of wetlands and their exceptional role in ensuring human well-being. Covering 18 million hectares, Polesia is not just Europe’s largest wetland area but also home to millions of people. The interdependence between Polesia's nature and the region's inhabitants is mutual: the quality of life, health and well-being of people are in many aspects determined by wetlands, while natural ecosystems may degrade and disappear without consistent protection measures.

Wetlands play a key role in storing and purifying freshwater, maintaining biodiversity and mitigating climate change. Some scientists say that life on Earth itself depends on wetlands because their ecosystem services are vital. The global problem is that they are degrading and disappearing at an extremely rapid rate – about 85% of the world’s wetlands have been lost, and this process has speeded up in the last 30 years due to human economic activities and climate change.

A vast belt of European lowland bogs that once stretched from France to western Siberia has been largely drained. In Polesia, however, a remnant of this ancient bog massif has been preserved. The inhabitants of Polesia are sometimes metaphorically referred to as ‘the people of the bog’. And life in the marshes is not easy at all: lack of arable land and communication routes, low crop yields, epidemics and other unfavourable factors led people to reclaim land from the marshes for economic purposes. Only in the last period of massive reclamation, from the 1960s to the 1980s, about 3 million hectares of wetlands were drained in Polesia. The results of this activity were not as expected: the newly reclaimed lands remained fertile and highly productive for several years. Over time, however, they created more problems than benefits and were often abandoned.

From improvement to destruction and back

Drainage of peatlands in Polesia has gradually led to desertification. In addition to depleted peatlands, the region has a large amount of peat soils, where the peat degrades very quickly under conditions of low groundwater levels. On 223,000 hectares of agricultural land, the soil has been completely destroyed, and almost the same area has been degraded by peat extraction, with the process of peat layer destruction continuing. If these anthropogenic changes are not stopped today, they will lead to very low yields and a rapid decline in biodiversity in the near future.

Draining wetlands has a negative impact on the ecology of adjacent areas. Wetlands lose their role as stabilisers of the hydrological conditions in the entire catchment area, small rivers and watercourses dry up and entire ecosystems are degraded. Recent research has shown that a 50-70 cm drop in groundwater levels results in a significant loss of biodiversity. It also increases the eutrophication of rivers and lakes. Every year, about 1.5 million tonnes of mineral and 700,000 tonnes of water-soluble organic substances flow from the drained areas of Polesia into the Black Sea via the Pripyat and Dnieper rivers.

Observing and comparing Polesia’s disturbed wetlands with intact ones, it is easy to see why preserving and restoring such ecosystems is an investment in the well-being of the people who live in this region.

Despite massive drainage, Polesia is still rich in undisturbed and highly functional wetland ecosystems. Bearing in mind that each hectare of intact wetlands absorbs up to 15 tonnes of carbon annually, this region makes a globally significant contribution to climate change mitigation.

At the same time, intensive land reclamation for peat extraction and agriculture is paving the way for the emergence of many areas that no longer provide any economic benefit, while emitting between 5 and 15 tonnes of carbon dioxide per hectare per year. Ecologists estimate that rewetting 200,000 hectares of disturbed peatlands that are not used for agriculture or peat extraction will reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 1.5 million tonnes of carbon dioxide annually. Remarkably, rewetting is one of the cheapest ways to decrease CO2 emissions. Thus, wetland restoration and subsequent accurate accounting of greenhouse gas emission reductions in Polesia could be an important step for the countries that share this region to enter the global carbon market and sell free emission quotas.

Water vs. fire

The drained and degraded agricultural land, which is increasing in area, is a source of another negative phenomenon – wildfires. Initially, groundwater levels have been lowered artificially, but the situation is worsened by mild, snow-free winters and prolonged periods of warm, dry weather, which have become more frequent in recent years. Fighting wildfires costs a lot of money and resources every year. Peatland fires are particularly dangerous and difficult to detect and extinguish. Large fires are a burden on the economy, they threaten ecosystems and, of course, human life and health.

Particles released into the air by wildfires are a dangerous air pollutant. It was these fires that led to the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv, being at the top of the list of cities with the highest atmospheric pollution in 2020 and 2021. Of particular concern are large fires in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone, a highly contaminated area. After being drained several decades ago, its territory burns very often, releasing not only greenhouse gases but also radioactive substances, which then spread with the wind and pose a threat to human health.

Experts say the optimal solution to the problem of Polesia’s devastating wildfires is obvious: water can’t burn, so it’s necessary to bring water back to the drained areas by restoring natural or near-natural hydrological regimes. A study carried out as part of our project has shown that by preserving and restoring intact, well-hydrated peatlands, we can create natural barriers to large, devastating fires.

Natural hydrological regimes allow wetlands to perform one of their most important functions – the accumulation and purification of fresh water. The significance of Polesia’s water resources is immense. Feeding major rivers such as the Pripyat or the Dnieper, Polesia’s wetlands provide drinking water for two thirds of the Ukrainian population. If the groundwater level in the marshes drops, it could be catastrophic for millions of people. But local rural communities in Polesia are already experiencing the consequences of systematic wetland drainage. Water levels in people’s wells are falling, and the lack of water for daily needs is evident. Regional and local authorities often try to solve the problem by building artificial reservoirs, but it costs millions of dollars to build and operate them. Experts estimate that the cost of equipping a small artificial reservoir would be enough to rewet all of Polesia’s disturbed wetlands and provide a natural water supply for the region’s inhabitants. There would be no need for artificial reservoirs.

Natural resources: to take without destroying

Wetlands provide people with valuable resources that, if managed sustainably, can help to improve the well-being of local people and create new livelihoods and jobs. As noted above, the practice of draining wetlands for agricultural use brings only short-term benefits: within a few years, as yields decline or a peat deposit is developed, the area turns into wasteland. Nowadays, the idea of using the natural resources of Polesia’s wetlands without draining them, or after restoring the water regime, is becoming more common. Here are some examples.

Reeds grow abundantly in both undisturbed and restored wetlands. This plant can be used as a raw material for an environmentally friendly and efficient fuel that can potentially be supplied to small local businesses or power stations. Such an enterprise will be profitable if it serves customers within a radius of seanout 30 kilometres.

Cranberries are another important natural resource of the Polesia bogs. In the Almany Mires Nature Reserve alone, their annual amount is estimated at 6.7 thousand tonnes, of which up to 2.5 thousand tonnes are harvested. Every season, berry pickers earn more than 1 million dollars in total selling the cranberries harvested in the Almany Mires.

The wetlands stand out among other natural systems for their high biodiversity. Medicinal plants are particularly prominent. Many corners of Polesia, far from cities, transport routes and large industrial enterprises, are ecologically favourable enough for the collection of such valuable raw materials. According to the latest estimates, the potential for harvesting wild medicinal plants in Pripyat Polesia is currently used by only 1%.

The development of local industries for the processing of natural raw materials obtained from Polesia’s wetlands would create new jobs and produce goods with high added value. It would be economically viable and sustainable in the long term, as it focuses on a local renewable resource and doesn’t involve destroying the ecosystem for quick profits.

Polesia invites

Polesia’s wetlands with their unique flora and fauna are an extremely promising object of ecological tourism, which is often at the top of the list of visits for domestic and foreign wildlife enthusiasts. Innumerable birds, among them rare species like the Great Snipe, the Short-eared Owl, the Black Stork, the Common Crane as well as globally threatened species such as the Aquatic Warbler and the Greater Spotted Eagle, nest in the local wetlands. The river floodplains are the main resting place for millions of migratory birds in spring and autumn. This makes Polesia an important destination for birdwatching in Europe in any season of the year. Numerous free-flowing rivers with picturesque surroundings are very attractive for amateurs of ecotourism, and they can be especially impressive during seasonal floods.

Unfortunately, due to the war in Ukraine and the difficult political situation in Belarus, the full development of the tourist potential of Polesia is currently impossible. However, this promising area should by no means be discounted.

Unique nature – special people

Over centuries, Polesia’s wetlands played a crucial role in the formation of the local culture – from mythology and rituals to crafts and cuisine. Living in an exceptional landscape, which for centuries limited their communication with the rest of the world, the inhabitants of Polesia have preserved many phenomena of traditional culture which are now included in national and international lists of cultural heritage. Even today, in the 21st century, here we find a rich folklore, uniquelocal folk singing techniques and a very special dialect that some linguists consider to be a separate language.

Traditions like wild forest beekeeping, making a boat from a solid tree trunk and skillful water transport management, gathering and using wild medicinal herbs, making dishes from berries, mushrooms or river fish are transmitted from generation to generation only in close connection with the landscape and quickly disappear outside it. There is no doubt that the identity of Polesian culture and day-to-day life was formed largely thanks to the wetlands, and their loss would cause great damage to cultural diversity.

Wetlands have shaped the lives of local people for centuries and continue to do so today, although this is not always apparent at first glance. The dramatic consequences of the loss of these valuable and remarkable ecosystems are indeed visible. Once upon a time, people had to submit to the forces of nature. Today, we have many tools and technologies to subdue it. But we must be wise enough to use modern means to live in a healthy balance with nature, because we are more dependent on each other than ever before.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

Wins for Polesia in 2024: conservation as a long distance run

Wins for Polesia in 2024: conservation as a long distance run

2024 has passed, and we have to admit that conservation work in Polesia last year remained extremely challenging. The war in Ukraine has significantly affected decision-making processes and fieldwork opportunities. However, 2024 demonstrated that progress is made through consistent, incremental steps, just as it takes time for seeds to germinate and blossom. Seeing our efforts from years past paying off now, we are more patient as we continue to take new steps forwards.

Wetland restoration in Ukraine: the practical stage is even closer!

Throughout 2024, we have been working hard to prepare all the necessary conditions to start practical work on restoring disturbed wetlands in Ukrainian Polesia. Some time ago, potential restoration sites were identified and the relevant feasibility study developed. Of these areas we’ve prioritized four ones – two Ramsar sites in the Rivnenskyi Strict Nature Reserve and two ones in the Chornobyl Biosphere Reserve. Scientific justifications have been approved for all the sites, and engineering plans’ development will start soon. After its approval, we will be able to start construction work on the ground.

Hydrological indicators are critical for assessing the effectiveness of wetland restoration. We have assessed the baseline hydrological conditions at the restoration sites, including groundwater level fluctuations and drainage channels discharge. This became possible thanks to long-term hydrological monitoring programmes that have been held by both the reserves. To make further monitoring more efficient and informative, we are now establishing 15 more automated groundwater monitoring wells. The necessary equipment has been purchased for this purpose and delivered to the project protected areas.

High-quality facilities make the conservationists’ work more efficient. This is why we provide the protected areas in Polesia not only with hydrological but with other kinds of equipment. Last year, meteorological stations and optical devices for professional field researchers and birdwatchers went to the staff of eight Ukrainian protected areas.

Better protection and consistent management for natural values

Polesia is one of the largest wilderness areas in Europe. It still contains vast areas of intact nature, multiple and diverse habitats for numerous endangered species and rare biotopes, many of which are hard to find elsewhere on the continent. This vast region has yet to be explored in depth, and field researchers continue to discover new natural sites and objects of high conservation value in Polesia. Some of them, such as primeval forests or the habitats of some endangered species, can never be restored to their original state after being destroyed or disturbed. That is why we pay a lot of attention to giving such natural values a legal protection status, although this is a complicated and time-consuming process that sometimes takes years.

Natural values identified by the project team in Belarus before 2022 are keeping on getting legal protection status. In 2024, 317 habitats of 72 species of flora and fauna listed in the Red Data Book of Belarus were put under legal protection, just like 184 sites of typical and rare biotopes. The total area of the new protected sites amounts to 20 104 ha. All in all, 100 000 ha of natural areas have been taken under legal protection since the start of our project!

The new management plan for the Prypiacki National Park for the period until 2032 elaborated as part of the project back in 2020 has been adopted. This document sets out long-term goals for the management of the national park and contains complex and scientifically based measures to be taken to ensure the conservation of the most valuable natural objects and sites, biological and landscape diversity of this territory. For example, the new management plan provides for an increase in the total area of the national park and the area of its strictly protected zone, a ban on hunting spring birds in wetlands with a high level of protection, and a ban on hunting wolves in certain areas of the national park. The management plan also requires the restoration of disturbed natural complexes within the Prypiacki National Park. For instance, a scientific justification and a project for the restoration of disturbed wetlands are to be developed. It is important to note that, according to Belarusian legislation, compliance with an adopted management plan is mandatory. Thus, the development and adoption of such a document ensures a strategic and systematic approach to the conservation of a natural area.

With its impressive biodiversity, Polesia is home to many rare species. Interestingly, some of them were once thought to be locally extinct but then rediscovered in the region. This was the case with the Greater Noctule (Nyctalus lasiopterus) – Europe’s largest bat. This rare bat was rediscovered by the project team in Belarusian Polesia in 2017, after 70 years of absence. Later, during field surveys, several habitats of this bat were identified across Polesia. Thanks to those studies, the Greater Noctule will be included in the new edition of the Red Data Book of Belarus to be published in 2025.

Knowledge: learning new things, sharing with others

Over the years of our work in Polesia, we have carried out a number of field surveys and collected a wealth of data that continues to feed scientific research. For instance, it formed the basis of two scientific papers published in 2024.

Data collected from GPS-tagged Greater Spotted Eagles (Clanga clanga) nesting in Polesia allowed an analysis of the effects if the ongoing war in Ukraine on the migration patterns of the rare birds. The authors compared the birds’ migratory behavior in 2019-2021 and in spring 2022, after the start of military activity. They found that the birds showed significant route deviations and many of them avoided their usual stopovers in Ukraine. As a result, many eagles arrived at their nesting sites later than usual and the energy cost of their migration was higher.

In the course of unprecedentedly large camera trap survey carried out in Polesia as part of our project in 2020 – 2021 we obtained over 50 thousand pictures that are still being analyzed by the researchers. For instance, it became part of the international study focusing on diurnal activity of wolves and lynx along a gradient of human disturbance. It is the first attempt to find correlation between anthropogenic pressure and animals’ temporal behavior. The results of the study show that wolves change their temporal behavior in response to human pressure, but lynx don’t. This is most likely due to differences in their predation ecology. Understanding the daily activities of animals will help to develop effective strategies for carnivore conservation and the creation of a landscape of conflict-free coexistence between humans and wildlife.

Dissemination of knowledge about natural values and nature conservation keeps on being one of the project’s focuses. In the current circumstances, this work is being implemented only via online courses. Last year, our experts prepared and conducted five online courses focusing on invasive species, collection of data on tree species diversity, ecological education, citizen science and ecotrails development. Experts in nature conservation, education and culture, 288 people in total, attended the courses giving a very positive feedback to the teachers.

2024 has seen the continuation of the great systematic work started several years ago. It has also paved the way for a deeper understanding of the nature of Polesia and made practical steps for its conservation and restoration more reasonable and targeted. As we enter the new year, we are looking forward to making new practical steps in protection and restoration of natural areas of Polesia. We hope that our work for the sake of the Polesia’s nature and people will keep bringing new obvious and tangible results.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

Protection status matters: the case of Makove Bog – a virgin forest saved from destruction

Protection status matters: the case of Makove Bog – a virgin forest saved from destruction

The vast expanses of wild Polesia are full of surprises. Even after decades of research work, experts can’t claim to know the wildlife of this region inside and out. They are still discovering endangered species’ habitats (sometimes even those considered to be locally extinct), rare biotopes and, as it turned out, even vast areas of virgin forests! It is extremely important to give these natural values a legal protection status – this is a chance for them not to fall victims to human economic activity. The latest case from our project is a speaking proof to this.

The word ‘Polesia’ derives from the ancient proto-Slavic noun ‘les’ meaning ‘forest’. No wonder: even now, after centuries of natural and anthropogenic transformations, economic exploitation and urbanization, forests make up a significant share of the region’s area.

Among the diversity of Polesia’s ecosystems, old-growth forests stand out. There are a number of definitions of this concept, but they are essentially the same: a virgin forest is a forest of natural origin, formed by native species, with a complex age and spatial structure, capable of self-maintenance and self-regulation. The main criteria used to identify virgin forests are usually the presence of old trees, large amounts of dead wood in various stages of decomposition and the absence of economic activity for at least several decades. Of course, in all cases these forests are exceptionally rich in biodiversity, being the places where the rarest and most vulnerable species are concentrated. Old-growth forests perform a range of essential ecosystem functions: shaping weather and climate, purifying and conserving water, storing and sequestering carbon.

The most important characteristic of old-growth forests is their undisturbed nature. Any economic activity within their boundaries causes significant and often irrevocable disturbance, and sometimes even total destruction. Any form of logging, even the removal of deadwood or individual trees, actually leads to their destruction as old-growth forests. And once destroyed, virgin forests can never be restored, not even over many generations. The only possible mechanism for preserving such forests is a total ban on economic activity.

The total area of virgin forests in Polesia presumably amounts to several tens of thousands hectares. Interspersed with sparse forests on bogs and open bogs, which are also intact ecosystems, primeval forests form a complex spatial mosaic. There have been several attempts to find the last primeval forests in Polesia, and it is not an easy task. They are usually relatively small and fragmented, and the experts had to examine huge areas of forest affected by human activity in order to find the valuable areas subject to legal protection. Ukrainian environmental legislation provides for the creation of so-called “primeval forest natural monuments” with a total ban on economic activity.

In 2019-2021, an expedition to identify primeval forests in Ukrainian Polesia was organised as part of our project. During their work in the Rivne region, the specialists were surprised. Studying the documents describing the forest area known as Makove Bog, they expected to find a typical bog pine forest, with trees that were on average less than 110 years old and up to 15 metres high. But when they got there, they found that the trees looked much taller and older. In fact, core analysis showed that some were more than 150 years old. The almost complete absence of human activity and the abundance of dead wood proved that this was a natural, intact old-growth forest covering an area of 260 ha – a really large area for a Polesian primeval forest! Surprisingly, before the expedition, the area had never been explored and legally protected.

In December 2021, after completing all the necessary bureaucratic procedures, Makove Bog was granted an official protection status, with a total ban on any economic activity, including all kinds of logging, construction of any buildings, including elements of linear infrastructure, etc.

This case looked like a significant conservation victory, until at the end of 2023 the permit for peat extraction in Makove Bog for the next 20 years was auctioned by the Ukrainian government and bought for nearly $700,000. Unfortunately, this case is not unique in Ukraine: there have been other examples of the sale of permits for peat and amber mining in protected areas. Some of these deals have been cancelled by the Ministry of Environment, but not all.

Fortunately, the case of Makove Bog was brought to the attention of the specialised environmental prosecution service of the Ukrainian Prosecutor General’s Office. They stated that peat extraction in the area of designated virgin forest monument was a serious violation of national environmental legislation, as it would inevitably lead to the destruction of the unique natural object. The environmental prosecutors went to court and defended their position by proving that the use of Makove Bog for mining was illegal, using the high conservation status of the area as their main argument. The court agreed with their arguments and upheld the case. Now the prosecutors are also considering the establishment of protection zones around the nature monument.

We believe that this case is a significant conservation victory for Polesia’s wilderness, and a sound argument in favor of further identifying rare and valuable habitats and giving them legal protection. As we can see, without this work, unique ecosystems can be irreversibly disturbed or destroyed. And we may never even know it.

Our reference: more than 100,000 ha of natural areas in Polesia have been legally protected thanks to the efforts of our project.

Who’s awake in the woods at night? New study analyses the diel activity of carnivores

Who’s awake in the woods at night? New study analyses the diel activity of carnivores

The coexistence of wildlife and people in Europe's human-dominated landscape is a complex phenomenon. Protected areas are relatively small and they intermingle with areas of high human disturbance. This leads animals to use various adaptation mechanisms, including increasing their nocturnal activity. The recent study supported by our project analyses for the first time the diurnal activity of wolves and lynx along a gradient of human disturbance to reveal the correlation between anthropogenic pressure and animals’ temporal behavior.

A growing human presence in wildlife areas is particularly critical for large carnivores with large home ranges, such as the wolf and Eurasian lynx. Increasing nocturnal behaviour is one of the strategies that allows these animals to avoid risky interactions with humans. This behavioural adaptation mechanism has been described before. However, the new study is the first attempt to analyse the diurnal activity of the two carnivore species in a number of areas that differ in character and intensity of human presence – from areas of intense anthropogenic pressure to those where human activity is highly restricted.

Understanding the behaviour of large carnivores and the factors that cause them to change their mode of living is important from a number of perspectives. On the one hand, if human disturbance causes carnivores to shift their activity to the nocturnal period, this could affect their interactions with prey, with potentially significant consequences for the ecosystem. On the other hand, in human-dominated landscapes, nocturnal behaviour reduces negative human-animal interactions and thus benefits the conservation of carnivores by enabling their conflict-free coexistence.

Previous studies have shown that both wolves and lynx are predominantly nocturnal in Europe and have suggested that anthropogenic factors may influence their temporal behaviour. However, no attempt has been made to analyse the diurnal activity of carnivores in the context of a comparison between areas with different levels of anthropogenic pressure.

The authors of the new study suggested that both wolves and lynx would be more active during the day under conditions of low anthropogenic pressure and the probability of being active at night would rise as human disturbance increased. To test this hypothesis, the researchers analysed images from camera traps deployed at nine sites in six European countries with a gradient of anthropogenic pressure.

Remarkably, two of these sites are located in Polesia: the Ukrainian part of the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone and Pripyat-Polesia in Belarus. The lowest indices of human disturbance were expected to be found in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone (Ukraine), which was used as a baseline for wolf and lynx behaviour. Human activity in this area is extremely low due to decades of restricted human access following the Chornobyl nuclear accident in 1986. Camera trap data was also collected in central Belarusian Pripyat-Polesia (Belarus), Białowieża Primeval Forest (Poland), Tuchola Forest Complex (Poland), Bieszczady National Park (Poland), Skolivski Beskydy National Park (Ukraine), Bavarian Forest National Park (Germany), Plitvice Lakes National Park (Croatia) and Maremma Regional Park (Italy). All these areas are disturbed to a greater or lesser extent by various anthropogenic factors and their combinations, such as forestry, hunting, agriculture or tourism.

The data collected covers several years, from 2014 to 2022, focusing on the period from September to April, when large carnivores are usually monitored. Cameras were deployed along forest roads and trails used both by carnivores and people.

The analysed data set comprised more than 71,000 independent encounters, including 2,430 of wolves, 934 of lynx, 8,585 of prey species, and 59,408 of humans. The highest rate of human encounter was recorded in the Bavarian Forest National Park, while the lowest was in the Skolivski Beskydy National Park, followed by the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone.

The researchers found out that wolves in all the study sites were rather nocturnal than diurnal. As expected, wolves in our baseline study area in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone showed the highest levels of daytime activity. In Skolivski Beskydy and Białowieża National Parks, wolves were the second-most diurnal, while wolves in Belarusian Pripyat-Polesia were the most nocturnal. It is noteworthy that the latter area is characterised by the highest level of anthropogenic pressure and wolf hunting is allowed all year round. Apart from the human encounter rate, no human disturbance factors, such as human population or road density, explained higher activity of wolves at nighttime at the landscape level.

Lynx were consistently nocturnal in all study sites. However, lynx in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone were not the most likely to be observed at daytime: lynx in the Plitvice Lakes National Park had the highest probability of observation during the day, while lynx in the Bavarian Forest National Park were the most nocturnal. The data obtained indicates that the nocturnal habit of the lynx does not depend on the type and level of human disturbance.

The results of the study show that wolves change their temporal behavior in response to human pressure, but lynx don’t. This is most likely due to differences in their predation ecology.

Although they often prey on the same species, wolves and lynx have different hunting strategies. As cursorial predators, wolves rely on pursuit tactics. However, they can also use the stalk and ambush strategy, which is most effective in low light conditions. Wolves’ hunting success is generally highest at twilight, but it is likely that some wolves have improved their hunting success at daytime. In addition, the social behaviour of wolves can also influence their way of life, as they can hunt alone or in packs. As a predominantly solitary, ambush predator, the lynx fits well into the nocturnal-crepuscular niche because darkness allows it to implement its hunting strategy most effectively.

Areas of restricted human access in Europe are unlikely to expand in the near future. However, populations of large carnivores such as wolves and lynx are increasing and recolonising areas where they were previously extinct. This allows researchers to predict that populations of such species will continue to exhibit predominantly nocturnal behaviour in areas with high human presence, in order to minimise potentially dangerous interactions with humans. Understanding the daily activities of animals will help to develop effective strategies for carnivore conservation and the creation of a landscape of conflict-free coexistence between humans and wildlife.

Adam Francis Smith, Research and Monitoring Coordinator at the Frankfurt Zoological Society, one of the study’s authors:

“The most valuable result to me is managing people’s expectations of large carnivores. It is common to assume that wolves are just creatures of night time, but ultimately it is our impacts on the landscape, mostly during daytime, which confine them to night. Wolves are intelligent and adaptable to different human pressures. However, Eurasian lynx are mostly ambush predators, so being active at night fits their predation mode very well. Ultimately, this type of study wouldn’t be possible without access to great colleagues and data from a wide range of areas.

If we confine wolves to night because of human disturbance during the day, we can expect different behaviours. If we want to allow the full range of wolf behaviours, or in other words, to allow them to choose when to be active, we must decrease our disturbance in time as well as space. So, the most obvious next steps are to look at how these human disturbances influence other aspects of wolf and lynx biology. For example, is the hunting success lower in more nocturnal populations? What about the size of family groups? These are important questions for finding the balance between human disturbance and the capabilities and persistence of large carnivores in Europe.”

Smith, Adam & Kasper, Katharina & Lazzeri, Lorenzo & Schulte, Michael & Kudrenko, Svitlana & Say-Sallaz, Elise & Churski, Marcin & Shamovich, Dmitry & Obrizan, Serhii & Domashevsky, Serhii & Korepanova, Kateryna & Bashta, Andriy-Taras & Zhuravchak, Rostyslav & Gahbauer, Martin & Pirga, Bartosz & Fenchuk, Viktar & Kusak, Josip & Ferretti, Francesco & Kuijper, D.P.J. & Heurich, Marco. (2024). Reduced human disturbance increases diurnal activity in wolves, but not Eurasian lynx. Global Ecology and Conservation. e02985. DOI:10.1016/j.gecco.2024.e02985

Re-encountering Polesia’s nature and people: summer expedition of the Frankfurt Zoological Society

Re-encountering Polesia’s nature and people: summer expedition of the Frankfurt Zoological Society

At the end of July, a team from the Frankfurt Zoological Society visited several protected areas in Ukrainian Polesia. They met with local conservationists to discuss their current work and most pressing needs, got acquainted with some valuable natural objects, and inspected the areas waiting for consistent and professional restoration.

The cooperation between the Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS) and protected areas of Ukrainian Polesia has already become a good tradition. FZS has been providing material, technical and financial support to eight national parks and strict nature reserves in the region for several years. In particular, biodiversity monitoring has been carried out in a number of protected areas in Polesia, including using novel methods such as camera trapping and acoustic monitoring. Management plans have been developed for several protected areas in Ukrainian Polesia with the participation of FZS. A number of protected areas also received vehicles and other equipment to make the daily work of the staff easier and more efficient. Following Russia’s full-scale military invasion of Ukraine, some protected areas received additional funding to provide shelter for internally displaced people.

Michael Brombacher, Head of FZS Europe Department:

Polesia is one of the largest and most intact floodplain landscapes in Europe with numerous rivers, peatlands and lakes. It is home to large mammals such as moose and lynx, and is important for migratory birds. But the wetlands are also vital to the people of the region, providing food and possessing great tourism potential. Polesia is well protected by a number of nature reserves and national parks, some of which have only recently been established, such as the Pushcha Radzivila National Park. FZS stands by the protected areas in the Carpathians and Polesia during the current difficult economic period caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In doing so, we are helping the dedicated staff of the protected areas to continue their important work – keeping Ukraine’s nature intact.

At the end of July, a team from the Frankfurt Zoological Society took part in another expedition to national nature parks and nature reserves in Polesia to learn about their work and understand the needs of the institutions.

Despite a lack of staff, scarce funds and the war in the country, the conservationists of Ukrainian Polesia are doing their best to protect and promote the local nature and to tackle the various problems and challenges they face in their work. For example, rubbish collection points in the Nobelskyi National Park help to keep the recreation areas clean. Bird watching towers in the Prypiat-Stokhid National Park and the Cheremskyi Strict Nature Reserve attract nature lovers. An ornithological trail above the water in the Poliskyi Strict Nature Reserve is designed for eco-educational purposes and makes it possible to combine recreation and nature observation.

Volodymyr Dikovytskyi, Director of the Nobelskyi National Park:

Without the support from FZS, the Nobelskyi National Park would not be able to function at all! And this is no exaggeration. Since the establishment of the Nobelskyi National Park in 2019 and to this day, 80% of the material and technical base that the park has, including machinery, equipment, supplies, etc., have been provided by the Frankfurt Zoological Society.

Every encounter with Polesia’s intact wilderness is energising and inspiring. This visit was no exception! The participants of the expedition enjoyed the view of the vast wetlands and forests, the purity and freshness of the lakes. They observed the nesting sites of the rare Greater Spotted Eagle and visited the Juzefin Oak, believed to be one of the oldest trees in Ukraine.

While in some places the beauty and power of Polesia’s nature is striking, in others it is clear how much it needs help when it suffers from human activity. The participants of the expedition paid particular attention to the natural sites that have been affected by various anthropogenic factors. In the Nobelskyi National Park, for example, the guests were shown the traces of amber mining. This illegal activity has led to a serious disturbance of the hydrological regime, massive deforestation and the destruction of the fertile soil layer. Such areas can be recultivated, but it takes a lot of special knowledge, effort and certainly time.

Drevlianskyi Strict Nature Reserve and Pushcha Radzivila National Park are suffering from wildfires – the expedition participants saw large areas of forest destroyed by flames. Scientists point out that forests become less resistant to devastating wildfires when hydrological regimes are disturbed. This means that restoring the region’s wetlands can help to prevent large forest fires, which are one of the main threats to Polesia’s natural environment.

Water is the blood of Polesia, an inseparable part of its precious wetland ecosystems. Unfortunately, Polesia is losing water: this process is still going on due to intensive drainage in the past, especially in the mid-20th century. For example, in the Rivnenskyi Strict Nature Reserve, old drainage systems still influence the hydrological regime of the area and disturb the local ecosystems. Blocking the drainage channels would help to restore the surrounding wetlands to a near-natural state.

In the Poliskyi Strict Nature Reserve and the Chornobyl Radiation and Ecological Biosphere Reserve, the consequences of the alteration of the Zholobnytsia and Uzh riverbeds are obvious. In their natural state, Polesian rivers meander through the landscape, which creates favourable conditions for sustainable and harmonious wetland ecosystems. However, this harmony is destroyed when people start to straighten rivers for economic purposes – floodplain ecosystems are disturbed, and mires and peatlands are drained. Reverse transformation of riverbeds is possible, though labour- and resource-consuming.

Ecosystem restoration is now the focus of FZS’s work in Polesia. Some time ago, five drained wetlands were selected for further rewetting. And this summer’s expedition was another opportunity to compare notes with partners, identify priority tasks and needs, synchronise efforts and make the work on the ground more efficient.

Bird's-eye view of the warzone: the armed conflict in Ukraine impacts seasonal migration

Bird's-eye view of the warzone: the armed conflict in Ukraine impacts seasonal migration

Polesia is a stronghold for many rare species, including the Greater Spotted Eagle, which is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 20% of the European population of this species breeds in Polesia. No wonder that these birds have been in the spotlight since the beginning of our project. To learn more about their behaviour, migration patterns and wintering grounds, we tagged more than 20 Greater Spotted Eagles with GPS transmitters as part of our project. No one could have even imagined that the data obtained in this way would be used to analyse the impact of a bloody military conflict on these rare birds.

On the 24th of February, 2022, the Russian Federation started its military invasion of Ukraine. And on the 3rd of March, the first of 19 GPS-tagged Greater Spotted Eagles began arriving in Ukraine from the south, on their annual migration route to breeding grounds in the Belarusian part of Polesia. Meanwhile, military activity was spreading, affecting more and more areas. Although shocked by the events, researchers realised that this was a rare opportunity to obtain information of unique scientific importance. Wars obviously have an impact on wildlife – both directly, via mortality and environmental damage, and in many ways indirectly. But it is always difficult and dangerous to study these processes, let alone obtain real-time data. To date, most such studies have focused on sedentary species living in areas close to military training sites. At the same time, the impact of military conflicts on migratory birds has been poorly understood, despite the fact that the world’s major migratory corridors cross several active military conflict zones.

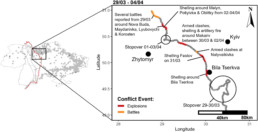

The researchers tracked the migration routes of GPS-tagged Greater Spotted Eagles in the spring of 2022 and then correlated this information with data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) project. They found out that the birds showed typical migratory behaviour before arriving in Ukraine. However, once they reached the active war zone, they started exhibiting different behaviour compared to previous years.

Prior to 2022, 90% of the birds observed stopped over in Ukraine on their way to their breeding grounds, whereas in 2022 only a third of the birds stopped over at the common sites.

The Greater Spotted Eagles also showed significant route deviations.In addition, they migrated 20-30% slower and their migration through Ukraine took longer than in previous years (25% longer for females and 50% longer for males). As a result, the birds arrived at their breeding grounds later than usual, and the energetic cost of the migration increased. The authors of this research suppose that the changes in the birds`behavior caused by the military conflict could have sublethal fitness effects on the Greater Spotted Eagles.

The authors of the study cite a female Greater Spotted Eagle nicknamed Denisa as an example of non-typical migration behavior in spring 2022. She was exposed to numerous war events. After witnessing artillery fire and explosions along her route, she moved westwards to avoid crossing active conflict zones. The graph shows Denisa’s migration route and the war events she faced on her way.

Previous studies have shown that numerous and varied anthropogenic disturbances, especially those that are unexpected, can cause severe and prolonged stress that significantly alters the behaviour of wildlife. However, armed conflicts involving shelling and explosions, mining, heavy traffic, human migration, direct habitat destruction, wildfires and many more far exceed any other anthropogenic activity in terms of intensity. Such extreme disturbance can potentially have long-term effects on sensitive Greater Spotted Eagles, causing deterioration in their body condition and affecting the reproductive success of the birds breeding in and around conflict zones. This is particularly important given that their breeding success is comparatively low on average.

The authors of the paper emphasise that human conflicts can have serious direct and indirect effects on migratory species, not only in Ukraine but also in other war zones along globally important migratory routes, which could be detrimental to hundreds of endangered species and millions of migratory birds.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

The Chornobyl Exclusion Zone: Polesia’s complex legacy

The Chornobyl Exclusion Zone: Polesia’s complex legacy

Polesia is known as a vast area of rich and diverse wilderness, however, not everyone realises that it was this very land that experienced one of the worst ecological disasters in history. It is Polesia that hosts the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone – the abandoned area created as a result of the sadly remembered nuclear accident. The complicated processes that have been taking place there for almost four decades, including the unguided rewilding of the abandoned areas and the lasting impact of radioactive contamination, continue to attract the attention of scientists and conservationists.

On 26 April 1986, a terrible accident occurred at the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant. As a result of an explosion, one of the nuclear units was destroyed. This led to the release of radioactive contaminants that quickly spread across the territories of the former Soviet Union and Europe. More than 115,000 people had to leave their homes in the 470,000-hectare area around the plant because of the severe contamination. This still uninhabited area, known as the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone (CEZ), is shared by Ukraine and Belarus. It is unevenly contaminated with radionuclides, including strontium, caesium, aluminium and plutonium, while many other radionuclides have already decayed. A special concrete confinement was built over the destroyed nuclear unit of the power plant to prevent further leakage of radioactive material.

In 1988, the Polesia State Radioecological Reserve was founded in the Belarusian part of the CEZ. In 2016, the Chornobyl Radiation and Ecological Biosphere Reserve was established in Ukraine. These scientific and conservation institutions carry out research work and monitoring of wildlife in the territory of the Exclusion Zone.

In the immediate aftermath of the accident, local wildlife was exposed to extremely high levels of radiation. This had a devastating effect on vegetation and wildlife, especially in the immediate vicinity of the destroyed reactor. Today, however, most of the CEZ has nothing in common with a nuclear desert. In fact, under conditions of almost total absence of anthropogenic pressure, wilderness has begun to reclaim areas that were once densely populated and intensively used for agricultural purposes. For instance, censuses have shown that red deer, roe deer, elk, and wild boar are increasing in the abandoned areas. The introduced Przewalski’s horses and European bison formed stable and growing populations. According to the same research, the number of grey wolves in the CEZ is several times higher than in some uncontaminated nature reserves in Belarus. Other research supported by our project showed that the Eurasian lynx density in the CEZ is significantly higher than in some other protected areas. Remarkably, camera traps deployed in the Chornobyl Radiation and Ecological Biosphere Reserve have detected the presence of brown bears in the Exclusion Zone.

In the 20th century, the once swampy areas of today’s CEZ were heavily drained for agricultural purposes. Soon after the accident, numerous drainage canals in the Belarusian part of the CEZ were blocked to prevent wildfires and the discharge of contaminated water. And the landscape started to change: mires and forests are gradually replacing farmland. Subsequently, the species’ composition has changed, too. For example, the abundance of bird species dependent on humans or transformed landscapes decreased, while the globally endangered Greater spotted eagle is recolonising the CEZ. These predators, which depend on intact wetlands and are extremely sensitive to human disturbance during nesting, seem to have found ideal habitat here.

At the same time, some scientists are warning their colleagues against undue optimism and calling for other aspects of the problem to be considered. Some studies show negative long-term effects of low-level radiation on several generations of mammals. Others point out that some bird species have shown a tendency towards more frequent genetic mutations and reproductive difficulties in areas with relatively high levels of contamination. The abundance of various species – from soil invertebrates to mammals – is reported to have decreased in such areas. At the same time, opponents insist that radiation as such is not the only possible explanation for the observed adverse effects. The heated debate continues, but it’s clear that many aspects of post-Chornobyl biology remain to be studied.

The Russian military invasion of Ukraine in 2022 seriously disrupted research work in the CEZ. At the very beginning of the war, Russian troops occupied the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant and the adjacent areas of the Chornobyl Radiation and Ecological Biosphere Reserve. As a result, the reserve’s property and equipment were damaged or destroyed, and the area is still mined. This makes any field work extremely difficult and dangerous. And yet, despite all the difficulties, activities in the CEZ haven’t stopped completely. The staff continue to carry out radiological and wildlife monitoring and are working to prevent the spread of radionuclides from the contaminated areas.

One of the most serious problems in the Ukrainian part of the CEZ at the moment is wildfires. Unlike the Belarusian part of the zone, the Ukrainian one has been heavily drained to prevent the spread of contamination by water flow. However, the result has been detrimental: frequent fires now cause severe air pollution and radioactive emissions. In 2020, 5% of the area was affected by flames. Fortunately, firefighters were able to prevent the radioactive waste dump from catching fire that year. Scientists emphasise that restoration of drained and disturbed wetlands is the most efficient nature-based solution to the problem of landscape fires. Large-scale wetland restoration in the Ukrainian CEZ is currently impossible. However, a site in this part of Polesia is among five areas selected for rewetting as part of our project. We hope to equip the reserve’s staff with the skills and knowledge needed to expand restoration in the future.

The Chornobyl Exclusion Zone is a unique area in Polesia, where the unintentional ecological experiment has been going on for almost 40 years and is unlikely to end in the foreseeable future. Paid for with the lives and health of thousands of people, numerous personal tragedies and harmful ecological consequences, it gives us a rare opportunity to gain valuable knowledge and reflect on the role of humankind in the environment of our planet.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).