Where the rare things are

Where the rare things are:

mapping habitat and improving protection of rare species in Polesia bear fruit

Good news for the wildlife of Polesia! Over the past year, 142 habitats of rare species in the Lelchycy and Stolin Districts of Belarus were put under legal protection. Their total area amounts to 6 372 hectares. Thanks to our project, 42 rare species now enjoy better protection, including mammals, birds, reptiles, insects, plants and fungi. Among them are the Greater Spotted Eagle and the Azure Tit, the Weasel and the Hazel Dormouse, the Pond Turtle and the Great Raft Spider, the Oblong-leaved Sundew and the Maitake mushroom.

Rare species of animals, plants and fungi that are endangered and subject to protection are listed in the “Red Book of Belarus”. But in order to bring their protection into effect, all individual habitats of these species must first be identified and registered. This is a complex procedure and requires the participation of a number of specialists and institutions. The identification of habitats usually happens within the frame of scientific field surveys, forest management or environmental protection actions. Sometimes also lay persons detect and report habitats, however, only qualified specialists can document them for the official registration process.

The next step is the preparation of a “habitat passport”. The passport needs to contain the name of the species, photos, description and coordinates of the location, the number of individuals, and an assessment of the overall state of the population.

Along with the passport, conservation obligations are issued. They list the necessary conservation measures and determine who is responsible for their implementation. Usually, it falls to the land user. This may be a legal entity (such as forestry), a sole proprietor or even a private person.

Passports and conservation obligations are sent to the local Inspection of Natural Resources and Environmental Protection, and then to the National Academy of Sciences for verification and approval. The agreed documents become the basis for the decision of local authorities on placing the habitats of rare species under protection. Now, conservation measures are legally justified! Their implementation is monitored by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Protection and its local offices.

What exactly needs to (or mustn’t) be done to save a rare species?

Obviously, protective measures are not the same for plants and fish, insects and fungi, reptiles and birds.

The survival of the European pond turtle (Emys оrbicularis) directly depends on the preservation of swamps and river floodplains. Where pond turtle habitats are registered, drainage for land reclamation is prohibited. Groundwork is not allowed either in order to protect eggs and young turtles. Strict regulations also apply to the management of water bodies: they mustn’t be artificially deepened and straightened, and aquatic plants may not be extracted or destroyed.

Larvae of a stag beetle (Lucanus cervus) need several years to develop during which they live on dead trees and feed on rotten wood. This is why the felling of old broad-leaved forests – especially oak-woods – the removal of dead trees and windbreak pose significant threats to this rare insect species. Cutting down old and withered trees, deploying chemicals or burning dry vegetation and logging waste are therefore forbidden in areas adjacent to stag beetle habitats.

Another “Red Book” species is the white-backed woodpecker (Dendrocopos leutocos). These rare birds build their homes in rotten trees and feed on insects they find under the withered bark. Therefore, not a single tree may be felled in territories where the white-backed woodpecker is found. To avoid disturbance during the nesting season, hunting and logging are prohibited near white-backed woodpecker habitats from March 1 to July 1.

The swamp violet (Viola uliginosa) can still be found in large parts of Europe, however, numbers are declining throughout its range. Swampy terrain and seasonally flooded floodplains are optimal for this plant, so it is not surprising that in Belarus it is most often registered in the region of Polesia. In or close to swamp violet habitats drainage for land reclamation, the usage of caterpillar vehicles or any other activities that can damage or destroy the live ground cover are prohibited. Wood cutting can be carried out to a limited extent, but only if there is a stable snow cover.

We keep on searching, registering and reporting habitats of rare species of flora and fauna in Polesia to ensure their effective protection.

The top photo shows a Purple Emperor butterfly. Photo credit: Daniel Rosengren.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

River flow affects high-energy Great Snipe lekking

River flow affects high-energy Great Snipe lekking

New study shows link between seasonal floods and Great Snipe lekking condition. The long-term research conducted at Turov Meadows in Belarus found that river water level impacts the ability of the birds to meet the high energy demands of their breeding competition. A finding that reinforces the need to maintain natural river flow in Polesia.

Each spring Great Snipes congregate in Eastern Europe’s wetlands. Rich in floodplains and marshes, Polesia offers key habitat for the waders. The birds are now listed as ‘near threatened’ with populations still in decline. A central cause of this decline is the loss of suitable habitat for breeding and nesting.

Earthworms make up 90% of the diet of Great Snipes. The location and accessibility of the worms impacts the waders’ ability to meet their resource requirements. Earthworms migrate between different soil depths depending on soil moisture. Waders rely on a rise in the water table which leaves only a narrow unflooded soil layer, forcing earthworms to congregate near the surface. Here, the birds can easily probe the softened soil with their curved beaks to extract the worms.

A good supply of food is of particular importance during the breeding season. Selection in Great Snipes takes place through lekking – a competitive behaviour exhibited by males in order to attract a mate. About 10 to 20 male Great Snipes gather in a lek where they elongate their bodies, inflate their chests, perform special songs, and flutter their wings. From time to time sparring between the males occurs.

Females choose a suitable mate based on physical attributes, but also the vigour and stamina exhibited during their lek performances. In general males with better body condition can expend more energy on lekking, winning greater attention from the females. But success in this competition demands great strain: during the mating season male Great Snipes spend four times more energy than usual. They lose about 5% of their body weight in just one night of active lekking. To regain strength and maintain good body condition during this period they must feed intensively.

A long-term study (2001-2020) at Polesia’s Turov Meadows measured Great Snipe body size and condition and compared this data to fluctuations in the water level in the Pripyat River over time. As snow melt fills the Pripyat in spring, the water table across the floodplain rises pushing the earthworms closer to the soil surface.

At a water level in the river of 220 to 420 centimetres the body weight of male Great Snipes remained relatively stable. The layer of un-flooded soil in these conditions remains deep; the availability of prey does not change significantly. But as the water rises from 420 to 490 cm an increase in the weight of Great Snipes was observed. When the water level reaches this range, not only is the top layer of soil rich in earthworms, but also the flood loosened soil makes it easier for snipes to search for food. In such conditions, birds do not have to fly far from the breeding areas in search of feeding grounds, thus saving energy.

After the water level in the river exceeds 490 centimetres, the body weight of male Great Snipes began to decline. Under these conditions large areas become flooded, causing the earthworms to leave. The relatively short length of the Great Snipes’ legs does not allow them to feed successfully on flooded sites. The birds have to fly further in search of higher ground. Such flights and growing competition in a limited suitable habitat increases energy needs, and body condition of Great Snipes deteriorates.

Water level can therefore indirectly impact the condition of lekking Great Snipe males.

The study suggest that hydrological management of grasslands in river valleys is especially important not only for Great Snipes, but possibly also for other earthworm-feeding species. Rivers should be left unaltered to allow natural spring floods to occur. Unfortunately, only 37% of all the world’s major rivers remain free-flowing, with dams, reservoirs, water extraction, and sedimentation disrupting the natural flow of the rest. These interventions, along with the conversion of floodplain wet meadows into intensively used agricultural land with excessive fertilisation and drainage ditches created to lower the level of groundwater, are the main reasons driving the loss of suitable breeding habitat for waders.

Top image shows a Great Snipe at Turov Meadows, Belarus. Photo credit: Daniel Rosengren

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

Achieving protected status for Polesia, Europe’s largest wetland wilderness

Achieving protected status for Polesia, Europe’s largest wetland wilderness

Following important steps taken in Belarus and Ukraine to protect mires at the heart of Polesia, conservationists want to see the region awarded UNESCO status

Ahead of World Wetlands Day (WWD) on 2 February, conservationists from Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders – an Endangered Landscapes Programme supported project– are calling for Europe’s largest wetland wilderness area to be included on UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

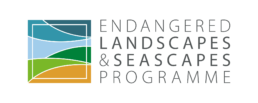

The recent signing of a resolution to establish the Pushcha Radzivila National Park in Ukraine and last year’s expansion of the Almany Mires Nature Reserve in Belarus have provided a much-needed boost to efforts to protect Polesia, a stunning transboundary region that straddles Belarus, Poland, Russia, and Ukraine.

But threats to Polesia from human activities still loom large. Deforestation, mining, farming, and plans to construct a major waterway through the region could lead to irreversible environmental damage, experts warn.

Attaining UNESCO status would see the central part of Polesia recognised alongside the Serengeti National Park, the Great Barrier Reef, and the Iguaçu National Park on the international list of sites with outstanding universal value.

Campaigners say that achieving designated protected status for the region at an international level would help ensure the future of the largest and most important inland wetland region in Europe. It would also protect the transboundary landscape’s essential ecosystem services, which underpin hydrology, store immense quantities of carbon, and have significant potential for ecotourism.

“We want to identify and classify key areas that are not currently recognised as protected landscapes, including primary forests, other forests of high conservation value, and sites home to rare birds and mammals,” says Olga Yaremchenko of the Ukrainian Society for the Protection of Birds (USPB).

“There is an astonishing diversity of plants and animals in Polesia. The presence of species such as the Greater Spotted Eagle, the Eagle Owl, the Great Grey Owl, the Pygmy Owl, the Black Stork, the lynx, and other rare species have been identified as key indicators when identifying priority areas for such protections.”

Protecting Europe’s Amazon

During the past three centuries, close to 85% of the world’s wetlands have been drained to provide land for housing, industry, and agriculture. Those that remain are vanishing three times faster than the world’s forests.

Large parts of Polesia, on the other hand, remain in near-pristine condition. It is one of Europe’s last truly wild places. Few places on the continent provide as much space for flora and fauna to survive and thrive.

Larger in size than an average European country, Polesia is often referred to as the ‘Amazon of Europe’. The region is home to an immense patchwork of forests, peatlands, floodplains, and rivers. In springtime, snowmelt turns much of the landscape into what looks like an endless lake.

These vast habitats provide sanctuary to a number of vulnerable species, including eagles, wolves, bears, lynx, and bison. Hundreds of thousands of migratory birds pass through the region. In the springtime, numbers of at least 150,000 – 200,000 Eurasian Widgeons, 200,000 – 400,000 Ruffs, and 20,000 – 25,000 Black-Tailed Godwits have been recorded in Polesia’s Pripyat floodplains alone. It is a key breeding ground for many globally threatened species.

However, like many wetland areas around the world, Polesia is threatened by human activities. Besides impacts from deforestation, mining, drainage for agriculture, and infrastructure developments, the adverse effects of climate change are further reducing the resilience of its environment.

Polesia has also come under intense focus as a result of plans to construct Europe’s longest waterway through the region. Known as the E40, the waterway would connect the Baltic Sea with the Black Sea, stretching some 2,000 kilometres from Gdansk in Poland to Kherson in Ukraine. The construction could destroy much of Polesia’s vast wilderness, with researchers predicting far-reaching implications for both humans and nature.

It has led to a race against time for conservationists to document the region’s biodiversity in detail, and make the case for its protection.

Important steps taken

Many parts of Polesia are of international importance for nature conservation and have been recognised as UNESCO Biosphere Reserves, Important Bird Areas, Emerald Network, or Ramsar sites. During the past 12 months, important steps have been taken at the national level to protect further areas.

At the turn of the year, a resolution was signed by Ukraine to establish the Pushcha Radzivila National Park in the heart of Polesia. Formed largely of bogs and transitional mires, the 24,000 hectare protected area secures better protection for the area’s wildlife, improves the connectivity of protected areas, and also provides important opportunities for local communities while keeping the carbon stored in its precious peatlands.

The move followed commitments by authorities in neighbouring Belarus to expand protections of the Almany Mires Nature Reserve in March 2021. Almany was expanded by 10,000 hectares, bringing the size of the reserve up to 104,000 hectares – roughly the size of Hong Kong. Research carried out as part of the Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders project, supported by the Endangered Landscapes Programme and Arcadia – a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin – helped to identify crucial habitats for rare wildlife in need of protection.

Together with the newly protected areas across the border in Ukraine, the area – which sits at the heart of Polesia – forms one of the largest peatland complexes in Europe.

“The pristine ecosystems and landscapes found in Polesia are, today, extraordinarily rare on a global level,” says Maxim Nemtchinov, a nature conservation officer at BirdLife Belarus (APB).

“A lot of work has been carried out by researchers and conservationists to characterise the flora and fauna in the region and ensure that this very special environment is protected from the threat of developments and construction. There are also crucial initiatives underway to restore parts of the ecosystem that have been damaged by human activities.”

Peatlands are the most carbon-dense terrestrial ecosystems. Globally, the carbon stored in them exceeds carbon stored in all other vegetation combined, including forests. Maintaining them is essential to help tackle the climate crisis. They also provide sanctuary for wildlife, spanning grey cranes, black grouse, beavers, otters, moose, bats, insects, and migratory birds.

Dianna Kopansky, who leads the Global Peatlands Initiative at UNEP, said “With most of Europe’s peatlands drained and degraded, this great wilderness is an oasis – for wildlife, people, and for our climate future. The work to expand protections and raise Polesia’s conservation status represents the action on the ground needed to fight the triple crisis we are facing and is a great contribution to the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration. The conservation and sustainable management of this critical trans-boundary landscape could not be more important for the people of the region.”

Historically, habitats such as peatlands have often been regarded as wastelands. As people don’t live on them, they can come under pressure from those wanting to turn them into farmlands or build roads across them. Many peatlands around the world are now severely degraded.

When peatlands are drained, the organic matter stored in them decays, releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere in the process. The dried land also becomes more susceptible to fires. The drainage of bogs and mires undermines the wider ecosystem health, its water flows, and the vital contributions they make to fresh and drinking water supplies.

A field biologist heads into the vast Almany Mires Nature Reserve to carry out biodiversity monitoring (left); data on migratory birds observed at Turov meadows is recorded (right). Photo credit: Evgeny Gostukhin

The first priority to protect these crucial habitats is to leave them as they are. That is why conservationists are campaigning to have these and other vital habitats across Polesia recognised with protected status at both the national and international levels.

Another priority is to restore those areas that have been degraded or damaged. Peatlands typically form very slowly, over hundreds or thousands of years. But by rewetting or revegetating damaged mires, it can revitalise their carbon storing abilities and reinvigorate their habitats for native plants and animals.

Although significant areas are already under formal protection, conservationists are calling for the central part of Polesia to be recognised internationally on the UNESCO World Heritage List. They say that this is necessary to ensure adequate protection of the region’s vulnerable species and wild landscapes, and recognition of its incredible natural beauty.

————————————–

This release is part of the Global Peat Press Project (GP3) campaign, bringing together international partners to highlight the importance of peatlands as vulnerable but valuable ecosystems. It is a coordinated media outreach from UNEP’s Global Peatlands Initiative (GPI) and the North Pennines AONB Partnership to promote the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021-2030). It was conceived to raise awareness and enthusiasm about the role of peatlands in climate action in the run-up to the UNFCCC COP26 in November, and has now pivoted to focus on the vital importance of peatlands for nature, aiming to build momentum and interest in advance of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) COP15 in April 2022.

A relay of stories from peatland projects worldwide, GP3 started with the UK, as the host of COP26, which took place in Glasgow, Scotland. The relay has already featured:

– the North Pennines AONB

– the Care-Peat project in Belgium

– NUI Galway/ Insight Centre

– Five EU transnational projects (Carbon Connects, Care-Peat, DESIRE, LIFE Peat Restore, and CANAPE)

– Bax & Company who straddle the UK, Spain and The Netherlands

– Ulster Wildlife

– The Lancashire Wildlife Trust

– The GPI and EUROSITE Peatlands Social Media Campaign

– NABU

– Moors for the Future Partnership

– Metsähallitus with its Hydrology LIFE Project

– Natural Resources Wales with the LIFE Welsh Raised Bogs Project

– Community Wetlands Forum and the Landscape Finance Lab

– Terra Motion

– Green Restoration Ireland Coop (GRI)

– a major restoration effort in Belarus recognized by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Protection of the Republic of Belarus

– a second release from Ulster Wildlife

– The World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) at the UN

– Griefswald Mire Centre in Germany

– Conservatoires d’éspaces naturels in France

– the Cairngorms National Park, Scotland

– a second contribution from the North Pennines AONB

– CINEA – LIFE

– Baltic Environmental Forum Lithuania

– Yorkshire Peat Partnership

– APB-BirdLife Belarus

and now the baton is held by Frankfurt Zoological Society.

Join us – share, learn, inspire, experience and act for peatlands, people and the planet. Follow and share using #PeatlandsMatter and #GenerationRestoration.

Notes to editors:

- Full Press Release

- Wild Polesia: wildpolesia.org

- Save Polesia: savepolesia.org

- World Wetlands Day: worldwetlandsday.org

- Global Peat Press Project: https://www.globalpeatlands.org/global-peat-press-project-gp3-campaign-kick-off/

About the Polesia Wilderness Without Borders Project

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia – a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS) and implemented in collaboration with APB-Birdlife Belarus, the Ukrainian Society for the Protection of Birds (USPB) and the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO).

About Frankfurt Zoological Society

The Frankfurt Zoological Society is an international conservation organization. From our offices in Frankfurt am Main, our staff coordinates projects in 18 countries.

Worldwide, 440 colleagues work for FZS conservation projects. Our common goal is the conservation of wildlife and wilderness. We work where national parks and wilderness areas need our support.

Our partners include local communities, conservation authorities, national park administrations, and other NGOs. We support our partners practically, unbureaucratically, and for the long term.

About the Global Peatlands Initiative (GPI)

The Global Peatlands Initiative is an international partnership launched at the UNFCCC COP in Marrakech, Morocco, in late 2016. Led by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), our goal is to protect and conserve peatlands as the world’s largest terrestrial organic carbon stock and to prevent it being emitted into the atmosphere. The GPI co-hosted the first ever Peatland Pavilion at COP26 in Glasgow in November 2021. Recordings of the sessions can be found here.

Article written by Adam Gristwood for the Polesia - Wilderness Without Borders project. Top image shows the Pripyat River floodplain. Photo credit: Viktar Malyshchyc

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

A New National Park for Polesia: Pushcha Radzivila

A New National Park for Polesia: Pushcha Radzivila

Polesia’s Pushcha Radzivila National Park secures better protection for wildlife and habitats, improves protected area connectivity, and brings sustainable development opportunities for local communities.

On the first day of 2022 the President of Ukraine signed a decree officially creating the new Pushcha Radzivila National Park. The Ukrainian Society for the Protection of Birds (USPB), as part of the Polesia – Wilderness without borders project, played a significant role in the creation of the new national park.

The park covers 24,265 hectares in Ukraine’s Rivne region. Together with protected areas in neighbouring Belarus, it forms one of the largest natural complexes of bogs and transitional mires in Europe. The area holds old-growth European spruce forests and a majestic 1,300 year-old veteran oak that measures 8 metres around the base of its trunk. Picturesque lakes and wilderness offer significant tourism development opportunities. These water bodies, together with the many swamps and wetlands in the area, are a vital water store for Polesia and Ukraine as a whole. These rare natural habitats also store massive amounts of carbon. Pushcha Radzivila forms part of the Pripyat basin playing a hydro-regulatory role for this mighty river which is the lifeblood of the Polesia region.

A central aim of our work is to increase the protection of these high conservation value areas. “Field experts identify and map primary forests and other high conservation value forests, as well as important sites for rare birds and mammals that lie beyond the boundaries of existing protected areas in order to apply for better protection for these sites”, explains USPB’s Olga Yaremchenko, who leads these efforts in Ukraine.

The presence of key species helps to identify important conservation areas – for example lynx, Greater Spotted Eagle and Black Grouse. Yaremchenko also emphasises that “a key component of our success in creating the Pushcha Radzivila National Park is the engagement of local communities who live nearby and understand the importance of nature conservation as the basis of a healthy life”. Thanks to the persistent support and lobbying of the communities, Rivne region managed to expand its protected area network, and thus increase the protection of Polesia.

In Pushcha Radzivila scientists have counted more than 450 species of plants and 230 species of animals, including 39 nationally endangered species. Grey Cranes and Black Grouse occur in the bogs and mires of the park. The protected area also harbours beavers, otters, lynx, moose, and almost a dozen species of bats.

Connectivity between the protected area network is enhanced – the park borders the Rivnenskyi Nature Reserve in Ukraine and Belarus’s Almany Mires Reserve in the north. The new park will thus also strengthen the protection of important wetlands in Rivnenskyi such as Perebrody Peatlands and Syra Pogonia Bog Ramsar sites.

Article written by Zanne Labuschagne, communications coordinator at FZS. Top image shows oak forests in Pushcha Radzivila National Park. Photo credit: Sergey Kantsyrenko

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

Wins for Polesia in 2021

Wins for Polesia in 2021

More than 10,000 hectares of the landscape gains better protection. Camera traps help uncover the area’s incredible wildlife, while local communities come together to protect it.

Bigger and better protection

The highlight of the year was by far the 10,000 hectare expansion of Almany Mires Nature Reserve in Belarus. The reserve now spans over 104,000 hectares (about the size of Hong Kong). Europe’s largest intact transition mire is found here. The area provides crucial habitat for globally threatened wildlife. This result hinged on efforts by local NGOs, and the Belarusian Ministry of Environment and National Academy of Sciences.

Better protection for the area was also achieved. Clear-cut logging is now prohibited across the whole reserve. Felling within the core zone is also no longer allowed, and a ban on hunting during the first half of May is in place.

In Ukraine a total of 640 hectares was granted an official protection status this year. Further expansions and the creation of a new national park in Ukraine are still in the pipeline.

Read more about the the next generation of protected areas in Ukrainian Polesia.

Restoring landscapes

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Watch FZS Belarus Programme Leader Viktar Fenchuk explain our approach:

Wildlife studies guide conservation

Large mammals

Across Polesia we continue to study wildlife at an unprecedented scale. The project deployed three hundred camera traps across 600,000 hectares of key protected areas in Ukraine and Belarus. This data feeds into the most extensive and systematic camera trap survey attempted in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone yet. Here – as a side effect of a terrible tragedy – nature has space. Data from the area will act as a baseline to assess wildlife presence and connectivity across Polesia to guide conservation.

The camera traps also provide fantastic images of European wildlife: herds of Przewalski’s horses; a close-up view of elusive lynx; and glimpses of wolf packs moving through the woods.

Greater Spotted Eagle

Greater Spotted Eagles from different populations migrate to different areas during winter. Males and females also differ in migration behavior. The results of a study co-authored by Dr Valery Dombrovsky and Dr Adham Ashton-Butt suggest that this migration behavior could worsen population declines.

The study included data from eagles tagged in Polesia. Belarusian breeding males mainly migrate to Africa and females to Europe. Threats faced by the birds, as well as the health of the wetlands they winter in, differ between Europe and Africa. This might already have led to sex-biased survival rates, and is likely to continue to do so in the future if wetlands in Africa become degraded or see more severe climate change impacts.

An imbalance between the number of male and female eagles could increase the chance of them breeding with Lesser Spotted Eagles. The latter are closely-related and more common. This would increase the risk of extinction of the vulnerable Greater Spotted Eagle.

Acoustic monitoring

We can now identify wildlife calls using a custom built-classifier. Since 2019 we have used acoustic monitoring to survey bats, birds, bush crickets and mammals. The approach is non-invasive, cost-effective, and allows simultaneous data collection from different taxa. Using this tool we can collect huge amounts of data in a relatively small amount of time, compared to conventional survey methods.

In 2021 acoustic recorders at 180 locations in Polesia generated millions of recordings. Classifying these recordings manually would be a near impossible task. To this end, the British Trust for Ornithology developed a machine learning algorithm to help sort recordings. The tool sifts out and identifies calls made by wildlife, separating them from other noises like wind and rain.

Sixteen species of bats have been surveyed so far and hundreds of thousands of recordings have been ascribed to species groups. The acoustic classifier is part of a larger European project to survey wildlife using acoustic monitoring.

Guardians of Polesia continue to grow

The ‘caretaker’ groups who volunteer their time to protect and promote nature in Polesia have more than doubled in Belarus alone. There are now over 260 people involved within 18 groups in Belarus and Ukraine. The pandemic continues to hinder some of their activities. Despite this, the groups held ten field camps (for example to collect litter), and 40 environmental education seminars. In Ukraine, new eco-trails are in place, and various lectures and birding seminars were held in both countries.

Polesia on TV

2021 saw some good coverage of the project. The German-French TV broadcaster ARTE carried out a filming trip and produced a feature ‘ARTE RE: Saving Europe’s Amazon. The project was also featured in the ARD series ‘Das große Artensterben’. A documentary about Polesia is now available to watch across the globe on the Waterbear Network.

Supporting Polesia’s protected areas

Four protected areas now have management plans in place, and a training course including over 20 modules is available for Ukrainian protected areas. Protected areas also received equipment, like GPSs, office equipment, weather stations and motorbikes.

Article written by Zanne Labuschagne, communications coordinator at FZS. Top image shows the vast Almany Mire Reserve. Photo credit: Viktar Fenchuk

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

Endangered eagle migration patterns key to their conservation

Endangered eagle migration patterns key to their conservation

The Greater Spotted Eagle is in trouble. Almost extinct in western Europe, Polesia is a stronghold for the critically endangered birds. Roughly 16% of the continent’s population is found in Belarus and 4% in Ukraine. Yet, even in Polesia’s vast network of forests and wetlands, numbers are dropping. Only in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone has the population increased in the last 20 years.

Why are we seeing these trends, and what could they be telling us about the health of habitat for the eagles? How does human disturbance influence these birds? Which areas are most favourable for them? We are looking for answers as part of our biodiversity monitoring activities within the ‘Polesia – Wilderness without borders’ project, funded by the Endangered Landscapes Programme.

New study uncovers eagle movements

A new study analysed tracking data from 28 adult Greater Spotted Eagles to see where the birds migrated to in winter. The paper, co-authored by Dr Valery Dombrovsky and Dr Adham Ashton-Butt from the project, included data from eagles tagged in Polesia. Wintering grounds – and the health and protection status of these areas – could be an important piece of the puzzle to conserve these precious birds.

Although wintering sites for Greater Spotted Eagles were relatively well known in Europe, eagles had also been sighted in the Middle East and Africa and it was not understood whether eagles from different breeding populations across Europe migrated to different areas. By tagging individuals from different breeding populations the study uncovered the extent of the Greater Spotted Eagle’s wintering range and how it differs between populations and sexes.

The eagles tagged in Belarus spent their winters in Southeast Europe, the Middle East or Africa. Males are more likely to winter further south than females – the majority of the male eagles from Belarus wintered within a narrow belt in South Sudan and Ethiopia. Females headed to the wetlands along the coast of southern Greece and Turkey. The winter grounds in southern Europe tend to be within a small number of protected areas – locations that the study indicates are crucial for the species. Only two of the 12 African sites are protected, both within the same national park.

Greater Spotted Eagles reliance on ecologically intact wetlands hints at one of the mechanisms of decline of this species, as the majority of wetlands in Southern Europe have been destroyed or degraded, with over 63% of Greece’s wetlands lost between 1950 and 1985. “The number of individuals wintering in a small area indicates that their wintering habitats may have been squeezed into fewer and fewer suitable locations”, explains Dr Adham Ashton-Butt from the British Trust for Ornithology.

The finding that Belarusian breeding males mainly migrate to Africa and Females to Europe could impact efforts to conserve Greater Spotted Eagles. The threats faced by the birds as well as the health of the wetlands they winter in differs between Europe and Africa. This might already have led to sex-biased survival rates and is likely to continue to do so in the future if wetlands in Africa become degraded or disproportionately impacted by climate change.

An imbalance between the number of males and females of the species could increase the likelihood of hybridisation with the more common and closely-related Lesser Spotted Eagle, increasing the risk of extinction.

A window into the lives of Polesia’s eagles – update from Ukraine

In Polesia a total of 21 adult Greater Spotted Eagles have been fitted with light-weight satellite tracking devices. This data has already contributed to several wider studies of the species. The teams in Ukraine and Belarus also use camera traps to look at the diet of the birds across a human-disturbance gradient. Here our aim is to determine how well the eagles are breeding and whether nest-site habitat has an impact on the survival of the chicks. Early findings suggest that eagle diet is more diverse in natural habitats than in transformed or disturbed areas, but we don’t yet know what implications this might have.

Field biologists from the “Ukrainian Society for the Protection of Birds” (USPB) – the project partner in Ukraine – monitor known and possible nesting sites in Polesia. Up to now this work is primarily carried out in Rivnenskiy Nature Reserve, and within the Somyne and Syra Pohonia complexes of bogs.

This summer, field expert Mykhailo Franchuk walked many miles in Rivnenskiy Nature Reserve to deploy camera traps and collect data. In total 12 Greater Spotted Eagle nests in the reserve were monitored. The data collected provides not only an indicator of the health of the species, but can also provide insights into the health of Polesia’s wetlands. The preferred nesting habitat for the eagles is mixed-forests on bogs and meadowlands. These areas provide ideal hunting grounds for the Greater Spotted Eagles to catch their prey, which include a variety of wetland birds, small mammals, snakes and amphibians. Dried-out or degraded wetland areas are unfavourable for wetland birds and may reduce eagle prey.

Article written by Zanne Labuschagne, communications coordinator at FZS. Top image shows a Greater Spotted Eagle in flight. Image credit: Daniel Rosengren

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

The Search for European Mink in Almany

The Search for European Mink in Almany

Last month, three biologists working with the Polesia – Wilderness without borders project set off into the vast Almany Mires. Their mission: to search for a particularly elusive species – the critically endangered European mink (Mustela lutreola). The species has not been sighted in Belarus for 20 years. Some suspect them to have been completely wiped out in the country, but if there is one place where these creatures could still be clinging to survival, it is the Almany Mires Nature Reserve.

The Almany Mires are still a rather poorly explored area. The reserve was expanded by 10,000 hectares in March this year – securing Europe’s largest intact transition mire and crucial habitat for globally threatened wildlife. The largely impassable and remote swamp could be acting as a refuge for the European mink.

What has led to this species’ disappearance from Belarus? In the 1930s, seven thousand American mink were brought to Europe, to the former USSR for the development of the fur trade. The American mink settled into its new landscape very well and soon began to outcompete the native European mink. Several decades later local hunters stopped seeing European mink. It remains unclear whether the species has now become extinct in the country.

Dmitry Shamovich , a zoologist and expert from the Polesia – Wilderness without borders project, set up 25 camera traps along the Stviga River and its tributaries in the hope that a European mink would be detected. Since minks are semi-aquatic animals, the camera traps were set up right next to the river and on drainage canals.

Dmitry explains that the European mink are not very mobile and usually do not venture further than a kilometre from watercourses. Some camera traps were also installed in the water, on metal and birch pegs, while others were fixed on trees on the river bank. Several weeks later the team returned to the Stviga by boat to collect and check the cameras.

On the shore, Viktar Fenchuk , an APB-Birdlife Belarus specialist and program coordinator of the Frankfurt Zoological Society in Belarus, explained:

“Stviga is the main water course of the Almany Mires Nature Reserve. Among the tributaries of the river there are many reclamation canals, which, although they are in a dilapidated state, still discharge water from the swamp, draining it.”

The project aims to strengthen the conservation status of the reserve. Wildlife is almost untouched here; there are very few places like this left in Europe. In addition, project specialists also monitor drained areas in the region and plan to block drainage channels and restore parts of the mire in the future.

Sadly, the first expedition in search of European mink ended without detection of the critically endangered species. The team will return in winter to again survey the Stviga and other parts of Almany, in the hope that the mink will still be found.

Article written by Zanne Labuschagne, communications coordinator at FZS.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

The Next Generation of Protected Areas in Polesia

The Next Generation of Protected Areas in Polesia

On the European Day of Parks we look to the ‘next generation’ of protected areas across the continent.

In central Polesia, one million hectares is already protected. This network of protected areas includes three national parks and several nature reserves and sanctuaries. In both Belarus and Ukraine, the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone – established after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1986 – is largely uninhabited by people. This area now provides a refuge for many species, in particular large mammals like moose, lynx, wolf and bear. Nevertheless, many of the landscape’s most valuable areas for nature remain unprotected, while existing protected areas are often up against shortfalls in budget and capacity for effective management.

The ‘Polesia – Wilderness without borders project’, with funding from the Endangered Landscapes Programme and Arcadia – a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin, works to protect biodiversity and re-establish connectivity between habitats for migrating wildlife in Polesia. This is achieved through support to protected areas; the establishment of new protected areas; or through the enlargement of existing ones, on 100,000 hectares of currently unprotected wilderness. These efforts bore fruit with a 10,000 ha expansion of the Almany Mires Reserve in Belarus in 2021. Almany now spans 104,000 ha (roughly the size of Hong Kong) – securing Europe’s largest intact transition mire.

Our approach to protected area expansion is driven by science. In close partnership with protected area authorities and national scientific bodies, we plan and implement large-scale, rigorous surveys across Polesia. This work includes mapping high conservation value forests, and field camps to identify key sites for biodiversity. Camera traps are also used to survey large mammals to better understand their abundance, population dynamics and connectivity across the landscape. The project further aims to increase international awareness of the core area of Polesia by nominating it for recognition as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and Biosphere Reserve and through the establishment of cross-border Ramsar sites.

Dr. Tatiana (Tania) Kuzmenko, from the Ukrainian Society for the Protection of Birds (USPB, BirdLife Ukraine), is the regional coordinator of the ‘Polesia – Wilderness without borders’ project in Ukraine. She plays a key role in overseeing protected area expansions and nominations across the project area. We speak to Tania about her work and exciting upcoming developments for the protected areas of this part of Polesia.

Watch a short video explaining Dr Tatiana Kuzmenko’s work to expand protected areas and promote transboundary collaboration:

What does your work as regional coordinator entail?

Tania: In my role as the regional coordinator I develop a basis for the expansion and improved management of protected areas. I oversee project implementation by field research experts; organise biodiversity monitoring to collect data that guides the expansion of the protected area network; support the creation of a conservation network (protection for nests and breeding sites in forestry zones); and submit nominations for the creation of new Emerald Network sites.

Polesia already has quite a developed protected area network – why do you feel the area needs more and bigger protected areas?

Tania: Polesia is a unique region, in particular in Ukraine, in terms of conservation of wild natural areas. It is one of the most valuable natural landscapes in our country. The region mitigates global climate change through the many benefits of its well conserved rivers, wetlands, mires and forests. Currently, a significant number of valuable and unique natural territories are outside of the Emerald Network of Areas of Special Conservation Interest and others lie beyond the boundaries of protected areas. These natural landscapes are threatened with disappearing due to threats such as clear-cut, industrial logging and amber mining. Therefore, it is very important to take these areas under the protected area ‘umbrella’ as soon as possible to give them legal protection. After this first step, we need to continue our efforts to ensure that parks on the map are also adequately protected on-the-ground.

How do you go about deciding how and where protected areas should be expanded?

Tania: We have identified high conservation value areas for biodiversity, in particular outside the existing protected area and Emerald Site networks. These high conservation value areas are mapped and analyzed, allowing us to identify selected areas of significant conservation value that need to be included in the protected area network. In particular, we look for the nesting sites of rare species – thus far we have identified 119 breeding sites of Common Crane and 50 of rare owl species, amongst others, which require improved protection. To detect these species, and to better understand the space they require to thrive, we conduct special surveys, using tools including acoustic monitoring and camera trapping. So far nomination forms for 13 new proposed Emerald Network sites have been submitted to the Bern Convention committee for approval; while we are also expecting a presidential decree on the creation of the new Pushcha Radzyvila National Park (24,000 hectares).

What are the most exciting results that are on the horizon for the project’s work on protected area expansion in Ukraine?

Tania: For me this would be the initiative of local communities to create the Slovechansko-Ovrutskiy Kriazh National Park in Polesia. The creation of this protected area is a grassroots initiative from the local people themselves, who want to have this national park and develop tourism in the area. This desire is manifested in concrete actions – restoration efforts have been launched by individual communities using their own resources, and the development of future tourist routes is already underway. There is no park yet, but people are already considering building the park office. USPB, as part of the ‘Polesia – Wilderness without borders project’, have been asked by local communities to support this process by preparing a package of documents to submit to the relevant authorities for the creation of this park.

What do you see as the ‘next generation’ of parks in the Ukrainian part of Polesia?

Tania: My hope is that in the future the national parks and nature reserves of Polesia will rise to a higher level of management, with ecotourism expanded and developed in a nature-friendly way, so that these areas will be comparable to standards elsewhere in Europe. I believe that this vision is achievable, in particular thanks to the support of our project. Protected area staff are gaining experience in modern research methods like acoustic monitoring, camera trapping, the latest techniques for processing and analysis of large datasets, and the use of Geospatial Information Systems. Existing protected areas in Ukraine are currently in difficult financial conditions, the project ‘Polesia – Wilderness without borders’ has provided equipment to enhance nature conservation activities. By being involved in such an international project, protected area staff are gaining valuable experience in effective park management.

Article written by Zanne Labuschagne, communications coordinator at FZS.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

Almany Mires Reserve Expanded

Almany Mires Reserve Expanded

Polesia’s vast Almany Mires Reserve expanded by 10,000 ha, securing habitat for threatened species.

A 10,000 hectare expansion of the Almany Mires Nature Reserve in the Belarusian part of Polesia was announced by the Republic’s Council of Ministries on March 3rd 2021. The reserve now spans over 104,000 hectares (about the size of Hong Kong) – securing Europe’s largest intact transition mire and crucial habitat for globally threatened wildlife. Together with protected areas across the border in Ukraine, it forms one of the largest natural complexes of bogs and transitional mires on the continent. The area stores huge amounts of carbon and forms part of the Pripyat river basin, playing a vital hydro-regulatory role for one of Europe’s last wild rivers.

Surveys strengthen case for expansion

The decision to expand Almany hinged on efforts by local NGOs, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Protection, and the Belarusian Academy of Sciences (NAS), supported by FZS. FZS partner APB-Birdlife Belarus has been working closely with the NAS and also the British Trust for Ornithology to carry out biodiversity monitoring and surveys in and around Almany since 2019. High conservation value forests were mapped and various field camps were completed to identify roosting trees for bats, nests of threatened birds, and other key sites for biodiversity. Acoustic recorders were deployed collecting thousands of hours of recordings and allowing researchers to identify the wildlife detected, in particular bats. Camera traps were also deployed to survey large mammals. This work, carried out as part of the ‘Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders’ project with funding from the Endangered Landscapes Programme and Arcadia – a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin, helped identify crucial habitat beyond the boundaries of the reserve. The preparatory work for these efforts was supported by the Claus und Taslimawati Schmidt-Luprian Stiftung Vogelschutz in Feuchtgebieten. The Belarusian Academy of Sciences submitted an expansion proposal, based on these results, to the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Protection earlier this year. The proposal was accepted in March.

Watch field biologist Stas Werdal from Belarus climb high into the canopy to deploy camera traps for the study of rare Greater Spotted Eagles (Clanga clanga):

Crucial habitat for rare wildlife

Almany harbours a rich diversity of species. Large predators like Eurasian lynx and wolf roam in search of prey, which also thrive in the area; while rare birds breed in the canopy of its riparian pine-dominated forests. Listed as a BirdLife Important Bird and Biodiversity Area, the summer months see one of Europe’s rarest songbirds, the globally threatened Aquatic Warbler, and the country’s largest Greater Spotted Eagle population move into the area to breed. During this time, thousands of other migratory birds also stopover in the area to rest and build up reserves for their winter flights. Other notable species found in the area include Black Stork, Terek Sandpipers, Golden Plover, Common Crane and Great Grey Owl.

Next steps for this important heritage

Although our partners in Belarus are celebrating this fantastic result, they are determined to achieve an even higher level of protection for this special landscape. The ‘Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders’ project is preparing a bid to designate a transboundary, 250,000 hectare UNESCO world heritage site in Polesia, with Almany at its heart. Conservationists also fear that the level of protection offered by the legislation of a ‘nature reserve’ might not provide adequate protection for this unique area. They plan to apply for the highest level of protected area status in the country – Strict Nature Reserve – which would better protect Almany’s forests from exploitation.

Article written by Zanne Labuschagne, communications coordinator at FZS.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

Polesia: a vast wetland wilderness

Polesia: a vast wetland wilderness

The world’s wetlands are disappearing three times faster than its forests, with 90% lost since the 1700s. These vanishing ecosystems play a crucial role in storing and cleaning water, mitigating flood damage, sustaining biodiversity, providing us with food and storing huge amounts of carbon.

Protecting wetlands

Polesia is Europe’s largest wetland wilderness and greatest floodplain region. Some of the continent’s last ‘wild’ rivers meander across the landscape, through a vast patchwork of carbon storing peatlands and forests, islands, lakes, bogs and wet meadows. Stretching across Belarus and Ukraine, spreading into Russia in the East and Poland in the West, Polesia covers more than 18 million hectares – about half the size of Germany. This is crucial habitat for struggling wildlife. The area harbours 60% of the world’s remaining aquatic warbler population and is the most important breeding ground west of Russia for the globally threatened Greater Spotted Eagle. Hundreds of thousands of migratory birds stopover in Polesia each year to rest, feed and breed while large mammals, like wolf, lynx and European bison, occur in significant numbers.

The ‘Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders’ project, through funding from the Endangered Landscapes Programme and Arcadia – a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin, is working to secure this rich natural heritage. By gaining a better understanding of the abundance and connectivity of the area’s wildlife our team are mapping priority sites. We are working with partners in Ukraine and Belarus to identify and establish new protected areas, and expand existing ones with the aim to create a contiguous network covering over 1 million hectares of ecologically functioning landscapes, including wetlands. Recognising Polesia’s global importance, the project is working on a UNESCO World Heritage Site and Biosphere Reserve nomination and driving the establishment of a cross-border Ramsar Site in Polesia. The Wild Polesia project also provides equipment and technical support to local authorities to improve the management of protected areas.

Restoring landscapes

The protection of surviving, intact wetlands is crucial, but unfortunately we have reached a point where we now need to go a step further. Altered and degraded wetlands and their vital ecosystem services need to be restored and brought back to life. Although much of Polesia’s wetlands remain largely intact and undamaged some areas have been altered. Over the coming years the Wild Polesia Project plans to restore over 6,000 hectares of mires and floodplains that were drained at the beginning of the last century.

Work has begun at the project’s first restoration site: Nerasnia in Belarus. Neresnia is a degraded transitional mire, part of the Wetland Topilovskoye, covering about 2000 hectares. This mire has been significantly altered by drainage channels and fires. These drainage channels will be blocked, in order to re-wet the mire. Monitoring hydrology, vegetation and invertebrates will help us assess and adapt our restoration efforts.

Watch FZS Belarus Programme Leader Viktar Fenchuk explain our approach:

Article written by Zanne Labuschagne, communications coordinator at FZS.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).