Insect monitoring

What insects tell us about the state of Polesia's wetlands

by Adham Ashton-Butt and Corinna Van Cayzeele

Alongside our restoration of mires in the core of Polesia, we are monitoring insect communities to understand the impact of our activities on ecosystem health. Our field team has just retrieved the first samples of insects from Malaise traps installed last month.

Polesia is among the largest landscapes of natural wetlands in Europe. However, the biodiversity and stability of this ecosystem complex suffers from the draining of mires. Drainage channels that were dug for the so-called “reclamation” of land for agriculture during Soviet times continue to drain large parts of Polesia’s wetlands. The drained mires make the area less resilient to droughts and fires and eliminate important ecological processes and habitat. Part of our project, therefore, is the restoration of 6,000 hectares of drained mires in the core area of Polesia.

But how do we know where restoration is needed and whether it has the desired effects?

To ensure that our activities benefit all aspects of the ecosystem, we need sound ecological knowledge. More specifically, we need data on insects. Insects are excellent indicators of ecosystem health as they are very sensitive to environmental change and respond quickly to disturbances or restoration, due to their short lifecycles. Therefore, certain assemblages of insects can be associated with different habitats, or different states of ecosystem health.

They are also at the heart of food webs that sustain the ecosystem, providing sustenance for birds, bats and small land mammals. We are looking at numbers and composition of insects to better understand

- the importance of undisturbed habitats,

- the impact of drainage, wildfires and seasonal changes, and

- The effect of our restoration activities on mire ecosystems.

In May, our field team started installing Malaise traps (tent-like structures that capture insects) to sample flying insects. The traps are being installed in near-pristine mires, drained mires (from heavily drained to slightly drained), restoration sites and sites affected by fire. We expect to catch mostly Hymenoptera (bees and wasps), Diptera (flies and relatives), Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies), some Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies), Ephemeroptera (mayflies) and some small Coleoptera (beetles).

Last week, the ecologists started collecting the first samples that had been caught. And with this starts the tricky part: species identification. Having specialist taxonomists identify each individual would be very time consuming. Moreover, many insects, especially many flies, have not yet been classified to species level. Therefore, identifying large numbers of samples across broad taxonomic groups is very difficult, if not impossible.

We are largely resolving this problem by using DNA metabarcoding to identify insects. DNA will be extracted from insect samples, sequenced to reveal its genetic code and identified by comparing against freely available genetic libraries. Some species will still not be able to be identified to species as their genetic code has not been stored in DNA libraries. However, these species can still be differentiated from one another genetically and can be labelled as “Species A” or “Species B”. This way, the presence of these species can still be compared across samples and sites. The biomass of each sample will also be measured, in order to compare the abundance of insects present between sites.

Sampling will continue over the next four years. Over this period, we will be able to analyze the response of insects to changes while taking into account different weather conditions between seasons and years. For example, it may be that in “good” years with cold winters and large spring floods, insect communities do not differ much between natural and drained sites. However, in years of drought, they might change more in sites that are degraded, as those sites do not have the environmental buffers provided by a “healthier” ecosystem.

Besides monitoring the effect of restoration, this study will help predict the consequences for biodiversity if draining is not stopped. We may lose certain types of insects and, consequently, associated plants and larger animals that depend on them for food and pollination. We will know the results after these four years. In the meantime, we will start blocking drainage channels to rewet mires and adjust our activities according to our findings along the way.

Dr. Adham Ashton-Butt is a Senior Research Ecologist at the BTO. Corinna Van Cayzeele is a Communications Assistant at FZS.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

Return of Greater Spotted Eagles

All tagged Greater Spotted Eagles have returned to their breeding grounds in Polesia

by Adham Ashton-Butt

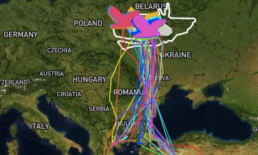

Last July, we satellite tagged the fifteenth Greater Spotted Eagle in Polesia. Since then, the eagles have spent the winter in Southern Europe or Africa before returning to their breeding grounds this spring and despite the chaos caused by COVID-19, data collection on their breeding ecology has begun. Luckily, social distancing is not too difficult in the remote mires of Polesia…

Greater Spotted Eagles are classed as endangered in Europe, with less than one thousand pairs remaining (IUCN 2015). Twenty percent of Europe’s Greater Spotted Eagles breed in Ukraine and Belarus, the majority of those in Polesia (78% breed in Russia and just 2% in the rest of Europe). Compared to Western Europe, where Greater Spotted Eagles are virtually extinct, Polesia still has large areas of intact forest and wetlands; the preferred habitat for this charismatic species. Worryingly, even in Polesia, eagles are declining, with fewer pairs breeding in the region each year.

As part of the “Wilderness Without Borders” project, we at the BTO are working with Belarusian eagle expert Valery Dombrovski and colleagues from the Estonian University of Life Sciences to devise a conservation plan to halt Greater Spotted Eagle decline.

The first task is to find out the reasons behind this decline. Are adults dying prematurely or are chicks failing to reach maturity, and why? We hope to answer these questions using a two-pronged approach:

Firstly, adult eagles are fitted with lightweight GPS tags, allowing us to see what habitats the eagles use most, where they go during the winter, how many survive and where mortality occurs.

Secondly, we are placing camera traps at nests along a gradient of habitat disturbance. This ranges from breeding territories in natural habitats to ones in habitats that are highly modified through human activity, such as intensive agriculture. The camera traps will record type and regularity of the food adults bring to their chicks and what proportion of chicks leave the nest successfully. This information will reveal how well chicks develop during the breeding season and whether the habitat surrounding the nest site affects the food availability and survival of chicks.

Greater Spotted Eagles are migratory birds and are known to winter in Southern Europe and Africa. However, before this project, very little was known about their migratory route or if there are any distinct migratory patterns or differences between populations.

Although it is too early to make any definitive conclusions, our early results suggest that it is problems on the breeding grounds in Polesia that are causing declines. Of the fifteen adult Greater Spotted Eagles tagged in 2017 (six) and 2019 (nine), all fifteen are still alive. However, none of the chicks from last year fledged and some adults did not even attempt to breed. This could have been because of food shortages or human disturbance near the nest. This year, with the help of extra funds from the British Ecological Society, we have placed cameras on twenty more nests. This is no mean feat, accessing a nest can involve a three-hour trek through a bog and a hair raising twenty metre climb up a tree, but it is key to understanding why chicks are not successfully fledging.

We will need to monitor tagged birds and their nests for a further three years before we are able to make robust conclusions about why Greater Spotted Eagles are declining. Only with this solid data, can we formulate an effective action plan to save this iconic wetland predator.

Dr. Adham Ashton-Butt is a Senior Research Ecologist at the BTO.

See where our tagged eagles have travelled here.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).