A bird's story told by a camera trap and a GPS-tracker

The adventures and dramas of birds: a story told by a camera trap and a GPS-tracker

Hi-tech equipment is helping our researchers gather valuable information about the endangered Greater Spotted Eagles. With the help of camera traps, we learn a lot about their behavior, diet and breeding, while GPS-trackers are revealing numerous patterns of the eagles’ migration. Ornithologist Valery Dombrovski has been researching Greater Spotted Eagles for decades. He knows how to systematize facts, numbers, graphs and trajectories… However, as a really sharp-sighted scientist, he can see whole stories behind this information. And here is one of those stories.

Male Greater Spotted Eagle Dzimon was captured and tagged with a GPS-tracker on the 9th of July 2020, in the eastern part of the Almany Mires in Polesia, not far from his nest. He wasn’t much different from other birds of the species: he hunted properly and raised a strong chick by autumn.

But something strange began to happen with Dzimon following spring, after he had returned to Polesia from his wintering site near the border of Sudan, Ethiopia and South Sudan. Having arrived at his nest, Dzimon his female in the company of another male. The couple had already renewed the old nest with fresh branches and lined it with green leaves to make the eggs’ incubation more comfortable.

The female’s behavior was not at all strange. She never knows if her old partner will return, and therefore she accepts courtship from any male who likes her. Usually, the new male leaves the nest in case the female’s old partner returns. At first it seemed like that was happening. Dzimon and the female visited the nest together, and the alien disappeared. But this only lasted for a couple of weeks.

On the 27th of April, Dzimon flew to the edge of his hunting territory and stayed at the same place for three days in a row. Unfortunately, the camera trap at the nest was not working at that time, and we don’t know what happened in the nest right before he left. But the eagle was confused, it was noticeable in his behavior. It seemed that he didn’t know what to do next. So, three days later, he took to the air and left those places. He never returned to his female and the future chick.

Dzimon started wandering. At the beginning, he headed to the north to hunt in an agricultural area near the town of Turau/Turaw, which was rich in field mice. Well refreshed, the bird headed east in a week’s time, reaching the town of Pietrykaw 70 kilometers away. Then he flew back crossing the river Ubarc and the Almany Mires and found himself on the bank of the Jaselda river not far from the town of Pinsk. On the 16th of May, Dzimon surprisingly headed to the town of Pinsk and stayed there, in the urbanized area, for more than a month! It looks like he was hunting right in private gardens on the outskirts of the town. In late June, the eagle changed his location again and flew to the Belarusian-Ukrainian border, where he stayed until the beginning of the autumn migration.

And what about the nest and the female? The new male that appeared in spring was still there. He spent the summer feeding the female and their chick that grew up and left the nest successfully in August. But why did Dzimon leave his nest? We can only guess. Maybe he lost the competition with a stronger and younger male, or maybe he guessed somehow that he would have to feed someone’s else chick… The bird’s thoughts will remain a secret.

During the spring migration of 2022, Dzimon arrived in Polesia very late – on the 19th of April. It was one of the latest known dates for the return of a Greater Spotted Eagle. He rushed directly to his old nest. Perhaps he was still hoping for a happy family life? Apparently, no one was waiting for him at home. Having spent about 20 minutes there, he flew on into the depth of the Almany Mires. Over the next month, Dzimon tried to settle down there. But he didn’t succeed, since the area was already shared by other nesting birds. Gradually, they drove him out further south, to Ukraine, where the density of the species is not so high. He spent most of the season close to the village Stare Selo in Ukraine. On the 25th of July, Dzimon flew kilometers to the south-east, to the Zhytomyr region, where he died three days later. No one knows what happened to him. The Ukrainian experts only found a tracker and the remains of Teflon straps that used to fix the device on the bird’s back. This was the end of Dzimon’s journey, during which he never found a new home.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

Through a camera trap: the secret life of rare eagles at arm’s reach

Through a camera trap: the secret life of rare eagles at arm’s reach

Sitting for hours in the bushes and marshes, peering through a telescope or a binocular - a decade or two ago, this was the only way to make scanty observations of nesting Greater Spotted Eagles. These birds are elusive and difficult to observe, especially during the breeding season when they are extremely sensitive to human disturbance. Nowadays, however, camera traps set up next to a nest can give us a valuable glimpse into the family life of these rare eagles and reveal many important and curious facts about them. We invite you to find out how we observed a nesting pair of Greater Spotted Eagles through the lens of a camera trap.

In 2021, the female Greater Spotted Eagle of unusual light colour returned to her nest on the 2nd of April. This individual is very remarkable: Greater Spotted Eagles with pale morph are very rare in the European part of their range, and this very bird became the first Greater Spotted Eagle with such a phenotype observed in the Belarusian Polesia. Will her chicks inherit the pale morph? We can’t predict that.

The male Greater Spotted Eagle – with rings on his legs and a GPS transmitter on his back – appeared two days later, on the 4th of April.

Greater Spotted Eagles often build their nest on a branch fork high above the ground, so that their home is hidden behind dense foliage. Typically, the same nest is used by the same pair of birds for several years in a row. Having returned home, the birds immediately started working hard improving the old nest. They carried new branches to their nest for more than 2 weeks. Compare its appearance before and after the renovation!

In late April, the female Greater Spotted Eagle spends a lot of time in the nest: she is about to lay eggs. A Greater Spotted Eagle usually lays from 1 to 3 eggs, with a break in time. And here it is! We observe the first egg on the 30th of April. On the 4th of May we see two eggs in the nest already.

Now, the incubation of the eggs begins. It lasts from 40 to 44 days on average. Previously, researchers supposed that only the female stays in the nest throughout the entire incubation period. But the camera traps pictures show that the birds take turns incubating the eggs. The female spends more time in the nest. However, the male often gives her time to hunt and stretch her wings. It is quite cold in early May, only 5-10 °C. The female spreads her feathers to keep herself and the eggs warm.

The male eagle feeds the female while she incubates the eggs. Information on the composition of the Greater Spotted Eagle’s diet is very important for the study and conservation of this species. And camera traps give us a chance to observe what the birds eat! This time, it’s a vole. Small rodents are common prey of the Greater Spotted Eagles.

At the beginning of June, our Greater Spotted Eagles look forward to the most exciting event of the nesting season: their chicks are about to hatch. The female’s powerful paws with sharp claws allow her to tear apart her prey easily. But look how delicately she holds the egg!

Finally, the long-awaited moment comes: the first chick hatches on the 8th of June after 5 weeks of incubation! The parents celebrate with big catch: this time, it’s a hare. While the female is busy with the prey, we can see the first hatched chick clearly – it is one day old!

On the 12th of June, we see the second chick free of its shell. But will it survive? Greater Spotted Eagles have a strong tendency to cainism: a second-hatched chick often dies within the first two weeks, and its death is directly or indirectly caused by the elder.

At about two weeks old, the chicks of the Greater Spotted Eagles are quite active, stretching their wings and crawling. The adult birds have to keep an eye on them all the time so that they don’t fall out of the nest.

Meanwhile, the male has to spend a lot of time hunting to provide food for himself, the female and their chicks. The camera trap captured rodents and a mallard chick among their prey. The female feeds the chicks in turns tearing the prey into small pieces. The older chick is bigger, stronger and more assertive. But the adults pay equal attention to the second-hatched one, too. Obviously, it has a good chance to survive!

The older chick is nearly 3 weeks old, with the first feathers visible among the down covering its body. Remarkably, the parents started leaving the chicks alone in the nest for short periods! The fast-growing chicks need a lot of food, so the adults have to spend a lot of time hunting. This time the male caught a weasel.

As the camera trap photos prove, the diet of the Greater Spotted Eagle is quite varied. In the photo below, the female seems to reproachfully look at the chicks as they turned away from the fish. But the next day we see a chick trying to eat a vole on its own while the adults are away!

When raising chicks, adult Greater Spotted Eagles permanently renew their nest with fresh branches of oak, alder and birch. In this way, the birds cover the remains of prey and droppings, keeping the nest clean.

It’s early July, and the first-hatched chick is one month old. The second one is just a few days younger, but the difference is still noticeable – they are growing so fast! Both chicks continue receiving equal care and nutrition, and it’s very likely that both will survive.

By mid-July, the Greater Spotted Eagles chicks have grown quite big and strong and no longer need the constant presence of their parents. Ornithologists choose this time to replace the batteries and SD cards of the camera trap on the nest and ring the chicks. Look, one of them has a new ring on its leg! The chicks often flap their wings in training for their first flight. But the female still cares for them tirelessly. The camera trap caught her shielding the chicks from the sun with her wings.

Most often, Greater Spotted Eagles hunt small mammals. However, the most part of the biomass consumed by these predators consists of birds. Sometimes, even large birds: the bones identified on these camera traps images belonged to a heron!

At the beginning of the nesting season, we guessed whether the new chicks of the pale female would be of the rare pale or typical dark colour. In the second half of the summer we can clearly see that they have inherited the morph of their father and have grown up to the typical dark colour of the Greater Spotted Eagle. However, there are known cases when chicks of two different phenotypes have been observed in the same brood!

By mid-August, the breeding story is over: the fledglings left the nest! They were last seen by our ornithologists in early September, when the young birds are usually quite independent. This is a remarkable story: both chicks survived and grew up! We hope that they are still well and that one day the rings will tell us more about them thanks.

Follow us on our Twitter account. There you will find more information about the wildlife of Polesia and more pictures from our camera trap surveys!

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

The sound of the wilderness

The sound of the wilderness

A pilot project in Polesia captures part of the biodiversity using audio recordings. This is a promising new tool for biodiversity monitoring.

Those carrying out biodiversity surveys in Polesia must not be squeamish. It is a wilderness area of superlatives: half the size of Germany, the predominantly peatland landscape stretches from Poland through Ukraine and Belarus into Russia. Rivers in their natural state, overflowing their banks in spring, meander through a mosaic of alluvial forests, bogs, oxbow lakes, floodplain meadows and mires.

Such large contiguous habitats have largely given way to agriculture in other parts of Europe. And these wet and boggy habitats are difficult to traverse. While our colleagues wade slowly across the mires to count rare birds of prey such as the Greater Spotted Eagle or set up camera traps to study wolves and lynx, swarms of mosquitoes and other insects are their faithful companions.

One of the main goals of our work in Polesia is to identify areas that are worth protecting. A better understanding of where there are gaps in protection and where priority areas lie will help us to support and justify requests to expand existing protected areas and designate new ones. Biodiversity and the presence of strictly protected species are among the key criteria.

However, population surveys are usually time-consuming. Additionally, nocturnal animals, such as insects or bats, which are difficult to find, are often overlooked, even though they usually have a high conservation status. Studying smaller animals such as bats, rodents and insects using conventional methods takes a lot of time, effort, patience and financial resources. Therefore, in Polesia we have turned to a new promising instrument for biodiversity research: acoustic monitoring. Bats and other species can now be identified using sound recordings.

Two years of passive acoustic monitoring

In the largest systematic survey of species diversity in Ukrainian and Belarusian Polesia to date, we carried out what is known as passive acoustic monitoring for two years. We recorded bats, birds, small mammals, bush crickets and some large mammals over an area of about 50,000 square kilometres, comparable in size to Slovakia. In this area, the recording devices were set up at 500 sites for four nights at a time. Thousands of hours of animal sounds have been recorded – day and night, in dense forests and extensive bogs and in every direction within a hundred metres of the recorder.

Shazam for animal sounds

The current result is around three million recordings with around 500,000 animal sounds. It would take years to filter out these animal sounds from other environmental noise and identify them individually. Therefore, our project partners at the British Trust for Ornithology have developed an automatic sound classifier. Similar to the mobile phone app Shazam, which can identify pieces of music based on a melody fragment, the new sound classifier is able to match recordings of animal sounds to certain species. The algorithm analyses the spectrogram, i.e. the visual sound image of the recording. It then searches for typical patterns according to known parameters and provides information about the type of sound recorded.

In this way, we can now automatically classify over 50 species of bats, birds, bush crickets and small mammals. To be on the safe side, these are then manually checked and the algorithm is improved where necessary. This allows us to record many species simultaneously, from the Great Grey Owl (Strix nebulosa) and the Pygmy Shrew (Sorex minutus) to bush crickets such as the Great Green Bush Cricket (Tettigonia viridissima).

This method of recording and monitoring the species is non-invasive as the animals are not disturbed compared to traditional methods. Bats, birds and insects do not have to be caught with nets and then examined and identified manually. In addition, acoustic monitoring is cost-effective as it allows the recording of different groups of animals simultaneously, and large amounts of data can be collected in a relatively short period compared to conventional recording methods.

The main objectives of the acoustic monitoring are to systematically map biodiversity throughout Polesia, identify habitats of particular importantance to different species, identify priority conservation areas and assess the impact of human activities such as drainage, fires and road construction on the biodiversity. The species lists also serve as a basis for formal applications to extend protected areas.

Elleni Vendras, Project Coordinator of “Polesia - Wilderness without Borders”

The top image features a night landscape of the Skrypitsa river floodplain in Polesia. Photo credit: Viktar Malyshchyc.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

Polesia, satellite view: innovative technologies for studying the landscape

Polesia, satellite view: innovative technologies for studying the landscape

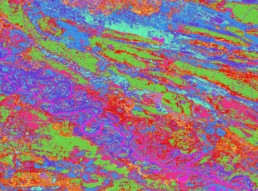

Conducting comprehensive research of a vast and varied landscape like Polesia is always a challenge. Fortunately, scientists nowadays have alternative methods that can reduce labour and time taken for field studies and make the experts’ work more efficient. For instance, the application of satellite data has made it possible to build the first landcover map for the whole of Polesia, facilitating mapping and analysis of large-scale fires that occurred in the region over the past 19 years. What are the pitfalls of working with satellite data? What should be considered when building similar maps for other regions? Let’s give the floor to one of the authors of these two studies – Dr. Adham Ashton-Butt, Senior Research Ecologist at the British Trust for Ornithology.

— Open-source satellite data can be extremely useful in obtaining environmental data over large areas and frequent measures over time. This is data that would often be too expensive or time-consuming to collect on the ground. There are limitations, however, as it is not always easy to see how data from satellites (spectral data) relates to “real” measurements on the ground e.g. moisture levels, growth of plants, soil carbon, or land cover. These relationships need to be estimated, which if not done well can result in large amounts of error.

— Your recent study analyzing the patterns of landscape fires in Polesia combines both conventional field surveys and innovative approaches that require special knowledge and skills to systematize and analyse large amounts of data. What specialists did you have to involve in your team to achieve the desired result?

— We had specialists who analyse fire relationships from satellite data, classify and utilise satellite data, and conduct statistical analysis and modeling of large data sets. Collaboration of people with special knowledge in different disciplines is very important for producing good and well-rounded research.

— Is it an easy task to “translate” the conclusions of data scientists into the language of environmental science?

— It was quite easy. In fact, environmental science and data science are very intertwined, so we understood each other very well.

— This study is the first one of its kind for the Polesia region. Did you face any difficulties along the way due to the specifics of the landscape itself or data related to it? What solutions helped you to overcome such difficulties?

— One of the biggest challenges was getting an accurate land cover map for Polesia. Existing regional maps only covered small areas, often not digitised and sometimes costly to access. Large free land cover maps (European or global maps, processed through machine learning) were inaccurate, or didn’t include important land cover types in Polesia like bogs and mires. We overcame this by building our own land cover map, by using ground-truthed data from our colleagues and then our own machine learning algorithms to process satellite data.

— Did you use a large amount of the necessary data from the ground for this research? How would you estimate the accuracy of the final results and are you satisfied with it?

— As for the amount of ground-truthed data, we used over 2000 polygons of manually verified training data. The accuracy of the land cover map was about 80%. We tested this by holding back a percentage of the training data and then checking this with the classified map. It’s always nice to increase accuracy, but overall we were satisfied with this.

— How can the methodology of this study be applied to other regions or landscapes? In this case, what basic principles will remain the same, and what aspects of the study will have to be changed and adapted?

— The fire database is global so this data can be extracted anywhere. The big limitations are the land cover maps that cover a region, these are often readily available in Europe or North America, but less so in other continents and regions.

— Are there any general recommendations for collecting preliminary data from the ground and creating a land cover map? What parameters and characteristics of a landscape, in addition to the space distribution of different land cover types, should be taken into account in order to most accurately identify the patterns of landscape fires?

— Training data evenly distributed across the region of interest is needed, as there can be spatial patterns of landcover types. For example, areas close together are more likely to be similar due to climate, geology, etc. Climate features (temperature, wind, precipitation) and topography are just some natural factors that are very important in identifying fire patterns. Human factors, such as settlements, land use intensity and land management (grazing intensity, farming practices, wetland drainage) should be certainly taken into account.

— Looking back, is there anything in your work that you wish you had done differently?

— It would have been great to have the outcome of building the land cover map of the project area as a priority at the start of the ELP project. This way we would have had more training data earlier in the process.

— What do you see as the prospects for the further application of this research?

— There are still many questions to answer. Do restored wetlands actually burn less? How long does it take them to get wet enough? How does this interact with the effects of climate change? It would be great to test our hypotheses on real restoration events.

The top image features an area in Almany Mires damaged by fire in 2018. Aerial photo by Ivan Murauyou.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

Meeting on the ground: disturbed mires of Ukrainian Polesia are waiting for restoration

Meeting on the ground: disturbed mires of Ukrainian Polesia are waiting for restoration

Experts from the “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” project and our partner organization the Michael Succow Foundation visited Ukraine. The visit was dedicated to the prospective restoration of disturbed and degraded mires in the Ukrainian part of Polesia. Its program included meetings with stakeholders, trips to protected natural areas and a round-table session.

The delegation’s members discussed the cooperation prospects with executives and employees of Cheremskyi, Rivnenskyi and Poliskyi nature reserves as well as the Chornobyl Radiation and Ecological Biosphere Reserve. In all these protected areas there are drained mires with good prospects for successful restoration – its feasibility was assessed by experts of the Michael Succow Foundation.

An important task was to listen to opinions of different groups of stakeholders. The position of specialists of the nature reserves is clear: they know the benefits of the mires’ restoration better than others and therefore highly appreciate the international assistance in organizing this work and demonstrate their willingness to cooperate. Their support is extremely valuable, just like the one of the State Agency of Water Resources of Ukraine.

At the same time, the opinions of the local communities are not always unambiguous. On the one hand, a stricter protection regime and rewetting of drained areas may mean certain limitations for economic activities of the local residents. On the other hand, lack of pure water caused by drainage is the argument that makes many people change their minds in favor of the mires’ restoration.

Olga Denyshchyk, scientific project coordinator at the Succow Foundation

"All the stakeholders in Ukraine are constructive, interactive and ready to cooperate more than ever before. This is truly inspiring. Peatland restoration is getting a strategic meaning, not only as freshwater reservoir, but also as a defense line. A lot of communities in Polesia are looking for investors and ready to consider any ecologically-sustainable offer. If you have something in mind, please do reach us out!"

Members of the foreign delegation accompanied by Ukrainian experts visited Cheremskyi, Rivnenskyi and Poliskyi nature reserves to learn more about them on the ground. Each of the reserves has its peculiarities, and the areas to be restored have different degrees of disturbance, spatial organization and features of drainage systems.

Mykhailo Franchuk, deputy director of the Rivnenskyi Nature Reserve:

“Mires make up 50% of the territory of the Rivnenskyi NR, and 20% are covered with fen forests. Over the past 100 years, they have been subjected to significant anthropogenic impact. I mean land reclamation, peat mining and illegal amber mining. As the climate changes intensified in recent years, the disturbed marshes with unstable hydrological regimes have become very vulnerable - the water disappears from wetland areas quicker than before. As a result, droughts, the transformation of typical marsh biotopes, and the biodiversity loss have intensified.

It is important for the Rivnenskyi NR to conserve the mires because it was created to protect the typical natural complexes of Polesia and is the largest marsh reserve in Ukraine. Currently, the reserve protects 13 communities of the Green Book of Ukraine. 53 species of plants, 106 species of animals occurring here are listed in the Red Book of Ukraine, 38 animals belong to the IUCN Red List.

The mires need saving! And restoration of the hydrological regimes planned within the framework of the project "Polesia - Wilderness Without Borders" is timely and necessary. I hope that our joint work will help to retain water in the mires and mitigate its loss”.

It has been decided that prior to the construction works, experts will conduct a one-year-long hydrological monitoring as well as peat layer analysis. It will allow assessing the present water levels in the project territories and then evaluating the efficiency of the restoration. The proposed monitoring methodology and further modeling based on the data obtained was elaborated and successfully tested by Polish experts.

During a round-table session that took part at the National University of Water and Environmental Engineering in Rivne, experts discussed the value, present state, threats and prospects of the Polesian wetlands. Among other topics, they touched upon the historical importance of mires as natural barriers during military conflicts which is unfortunately up on the agenda today. We hope that this aspect will lose its urgency very soon. However, mires in Polesia, being a source of drinking water for millions of people, an effective carbon storage and a hotspot of biodiversity, are worth being restored and preserved for generations to come.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

Natural hydrological regimes are key for Polesia's resilience to devastating landscape fires

New study: natural hydrological regimes are key for Polesia's resilience to devastating landscape fires

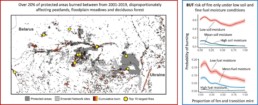

Landscape fires disproportionally affect areas of conservation priority but only under low moisture conditions - this is the conclusion of the new peer-reviewed study where scientists mapped and analyzed large fires that occurred over a 19-year period in Polesia, a region containing some of Europe’s last pristine peatlands and lowland forests in Eastern Europe.

Fires are of great concern to policymakers in the region due to the economic and health costs, and a lot of resources are used to suppress fires during hot and dry years. There are potentially natural solutions to fires, however, that could also benefit birds, biodiversity and climate issues. These ‘nature-based’ solutions include restoring drained wetlands. In this study, freely-available satellite data were used to explore the prevalence of large fires and the factors causing them. This allowed researchers to explore whether restoring the landscape’s wetlands could reduce the increasing risk of large, damaging fires as the climate changes.

This study identified five fires reaching more than 100 km2, a threshold often used to classify ‘megafires’. Frequent spring and summer fires predominantly started in agricultural areas, where farmers burn the land to clear it, both before planting and following the harvest. However, these fires often spread into neighbouring peatlands and floodplain meadows, endangering threatened wildlife, such as the Greater Spotted Eagle and Aquatic Warbler, and damaging a globally important carbon sink.

The largest fires burned in native deciduous forests, threatening protected old-growth oak and beech forests, which are more vulnerable and less likely to recover than more fire-adapted trees. Overall, more than one fifth of protected land burned. This is compared with 8% of unprotected land. One fire reached 97 km2 and burned significant areas of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, where radioactive contamination from the Chernobyl 1986 disaster is highest, and where the impacts of large fires on human health may be particularly severe.

The results of the study suggest that landscape restoration in Polesia’s wetlands would help to limit the spread and intensity of unnaturally large, damaging fires, while reinstating natural, periodic low-intensity fires, providing ecosystem benefits and supporting long-term carbon storage.

Throughout Europe, including in Polesia, years of drainage for agriculture and commercial forestry has created overgrown, drier landscapes that are more susceptible to fires. This study showed that open peatlands, meadows, and deciduous forests were far more likely to burn when moisture conditions in the soil and litter were low. In contrast, peatlands were very unlikely to burn under high moisture conditions. Preserving and restoring large, intact, well-hydrated peatlands would help to create natural barriers to large, severe fires, while reinstating periodic low-intensity fires. Doing so would provide ecosystem and conservation benefits, support long-term carbon storage and help tackle climate change, and protect human lives.

The article was originally published on www.bto.org.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

War beneath their wings: Greater Spotted Eagles are flying back to Polesia

War beneath their wings: Greater Spotted Eagles are flying back to Polesia

The spring migration of Greater Spotted Eagles has begun. Twenty percent of the European population of these birds breed in Polesia. Thanks to satellite tagging, we are able to keep a close eye on their movement. Now, researchers have special concerns about the migration of these endangered eagles: the birds’ path crosses Ukraine where the military conflict continues. While the war rages on the ground, the eagles fly their route undeterred.

Greater Spotted Eagles are returning to their nests in Polesia from the Balkan Peninsula, Israel, South Sudan, Zambia, and even South Africa. Every year, they fly thousands of kilometers to reach their breeding and wintering sites. Their journey is full of the expected difficulties and threats. However, they face another trial: the war is now right on their migration route. Polesia’s Greater Spotted Eagles faced this for the first time last spring. Ornithologist Valery Dombrovski, who has been researching Greater Spotted Eagles for decades and keeps a close eye on the GPS-tagged birds, shared some of his observations with us…

“Spring migration in 2022 was quite typical in terms of dates and average duration. But our close attention was riveted to Greater Spotted Eagles nesting in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone – they had to cross the Kyiv region where active hostilities were going on. One of them, a male by the name of Borovets, was the first to start on his way. He followed his traditional route through Odessa and Cherkasy regions. Borovets approached Kyiv on the 29th of March, at the very moment when the Russian troops withdrew under attack by the Ukrainian forces. Borovets stopped on the left bank of the Dnieper River to wait out bad weather: the sky was cloudy, and cold rain had started. The eagle spent the following day at the same place. Sounds of explosions were heard from far away – Kyiv was still being shelled. Could the bird tell these sounds from spring thunder? It is not really possible. On the 31st of March, when the sun shone again, Borovets rushed further north.

He flew above the eastern outskirts of Kyiv and then along the Kyiv Water Reservoir. With his sharp vision, it is likely he could observe long columns of military vehicles retreating from Kyiv, probably an uninteresting sight for the bird. Foul weather forced Borovets to stop again, now further up the reservoir, and about 20 kilometers from the Belarusian border. This time, he stayed in one place longer – from the 31st of March until the 3rd of April. It was quiet: explosions were no longer audible. The Russian troops had retreated from the Kyiv Region and the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone. Borovets fed happily on birds and mammals hiding in riverside reeds, and visited the farmlands around the neighboring villages.

On the 4th of April, a fair wind blew from the south and drew the clouds away. Just 4 hours later, the eagle reached his nest in the Polesie State Radioecological Reserve. Fortunately, the helicopters that were flying back and forth above the reserve every day during the past month had already followed the rest of Russian military units. Thankfully, Borovets could occupy himself with his “family” concerns. During the remainder of the 2022 season, he successfully bred a chick.

A female eagle, named Elleni, arrived in Ukraine much later. On the 4th of April, she stopped shortly in the Odessa Region. By the end of the next day, thanks to favorable weather, Elleni reached the western outskirts of Kyiv. There, she stayed overnight alongside the Irpin river. The fighting had stopped there several days earlier. The bird showed no unusual behavior. On the morning of April 6, she flew further north. Her flight path crossed now infamous places: Irpin, Gostomel, and Bucha where terrible massacres took place. Luckily, birds cannot understand such horrors. The next day, Elleni reached her nest, nearby to the nest of Borovets. Elleni’s breeding season ended with its own sadness, as her chick died in the middle of summer from an unknown cause.

In spring 2022, other Greater Spotted Eagles from Polesia flew across the Western part of Ukraine where there were no active battles. All the birds reached their nests successfully. The fastest one was Blond, on the 17th of March, he was already in his nest in Almany Mires. Most birds arrived later, in the first week of April. Vialuta was the last to return, arriving home on the 20th of April. By the way, this is the latest date of the end of spring migration for five years of observations.”

The war in Ukraine gave ornithologists not only food for thought, but also material for scientific research. We expect a research paper to be published analyzing the war’s impact upon the migration patterns of the Greater Spotted Eagles. In the meanwhile, though we can’t stop the war immediately, we hope for a safe migration back home for the birds – wild Polesia is waiting for them.

Top image fatures a Greater Spotted Eagle in flight. Photo credit: Daniel Rosengren.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

Decades without man: rewilding of the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone benefits endangered birds

Decades without man: rewilding of the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone benefits endangered birds

A new study shows the benefits of restoration in countering biodiversity loss. The paper, published in January 2022 by scientists from Belarus and Great Britain, used long-term raptor monitoring data from the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone. Data for the study was collected over 22 years, in parallel to passive rewilding of the abandoned area.

The accident at the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant in 1986 was one of the worst nuclear disasters that ever happened. When speaking about the long-term consequences, people naturally tend to refer to the negative impact on human health and on the environment, caused by the heavy radioactive contamination. However, there is at least one additional long-run side effect of this tragic occurrence that is often overlooked: the accident paved the way for an unparalleled case of large-scale rewilding of a settled region. On about 470,000 hectares of land that had formerly been densely populated and used for intensive agriculture, human activities ceased almost completely from one moment to the next. The people who once called this region home had to move away, the farmland was abandoned, and drainage canals were locked to prevent the spreading of wildfires and contaminated water. But the retreat of the population did not mean that all life had left the area. Nature took its chance and began to reclaim the territory, at its own will and pace.

This rewilding process has been observed by researchers for more than two decades. The findings are impressive: From 1999 to 2017, the wetland area increased by 680% and forest area by 14%. Now, more than 30 years after the accident, the territory looks like Polesian wetland habitats in northern Ukraine or southern Belarus, with typical seasonal floods and large mires.

Wilderness is advancing: who wins and who loses out?

The transformation of the animal communities was expected to be enormous after the massive decrease of human impact. Over a period of 22 years – from 1998 to 2019 – ornithologist Valery Dombrovski monitored population sizes, species composition, and habitat changes of birds of prey nesting in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone. Parts of this study were supported by the Polesia – Wilderness without Borders project. The study area spans over 14,700 hectares of former farmland that had been intensively used until 1986.

During the study period 13 breeding species of daytime predators were recorded, and both species composition as well as the number of individuals changed significantly.

For instance, the globally endangered Greater Spotted Eagle (Clanga clanga), which relies on wetland habitats to hunt and is very sensitive to human disturbance, had been locally extinct in the area at the time of the nuclear catastrophe. 33 years later, in 2019, four pairs were recorded at the study site, and at least 13 pairs were known to be nesting in the whole Belarusian part of the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone. Today, this region is the only part of the world where the population of this rare species is growing. The increase of wetland areas alongside low levels of anthropogenic influence in the Chornobyl area created favorable living conditions for the Greater Spotted Eagle, which may help save this threatened species from extinction.

Another (locally) endangered raptor that reacts sensitively to human presence is the White-tailed Eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla). Before the nuclear accident, this bird could not be found in what is today the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone. Only in 1992, White-tailed Eagles were first sighted here, and by 2010 their number had increased to 20 pairs. Unlike the Greater Spotted Eagles, White-tailed Eagles are non-migratory, so the availability of prey in winter is crucial for their survival. And here is how the true value of rewilding reveals itself: a functioning ecological community has returned to the area, composed of various species that sustain and support each other. Along with the birds of prey, top predators like wolves as well as their prey species (such as deer and moose) established viable populations, so that there is enough carrion for the White-tailed Eagle to make it through the cold season.

While the Greater Spotted Eagle and the White-tailed Eagle profited from the abandonment of the area, the scientists also observed decreasing populations of certain bird species. This applies to raptors that prefer hunting in farmland, such as Montagu’s Harrier (Circus pygargus), Lesser Spotted Eagle (Clanga pomarina), Honey Buzzard (Pernis apivorus), and Common Buzzard (Buteo buteo). Interestingly, at the beginning of the monitoring work in 1998, the population sizes of these species in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone were much higher than the regional average.

Overall, the study shows that the passive rewilding of ecosystems is a complex and lengthy process. Some species needed nearly two decades to build stable populations, and others, like the Greater and Lesser Spotted Eagle, are still adapting. The Greater Spotted Eagle started colonizing the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone only 15 years after humans had left. Therefore, a long-term dynamic monitoring is the only way to assess the restoration process and the development of species composition and population sizes. But it has already become obvious that passive rewilding can bring European lowlands back to a near-natural state – both on the ecosystem as well as on the biodiversity levels.

Top image shows the view of a reactor of the Chornobyl nuclear power plant from a fire watchtower. Polesia, Ukraine. Photo credit: Elleni Vendras.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

New partnership for the benefit of Polesia’s wetlands

New partnership for the benefit of Polesia’s wetlands

Our plans for wetland restoration in Ukraine are now supported by the Michael Succow Foundation. Through this new partnership, our colleagues are working on a feasibility assessment on prospective rewetting of drained peatlands in the Ukrainian part of Polesia.

Ecosystem-based approach: human-centered, nature-friendly

Founded in 1997, the Succow Foundation is engaged in projects of nature conservation, climate change mitigation, protected area management and sustainable land use on four continents covering a variety of landscapes. The organisation possesses extensive experience working in post-Soviet countries, including Ukraine.

Recently, the Succow Foundation team implemented a three-and-a-half-year-long project “Ecosystem-based Adaptation to Climate Change and Sustainable Regional Development by Empowerment of Ukrainian Biosphere Reserves”. The ecosystem-based approach leans upon protection, sustainable management and restoration of ecosystems in order to preserve or recover their natural properties. In turn, fully functional and sustainable ecosystems provide people with vital ecosystem services.

The benefits of ecosystem approach were demonstrated in practice in three pilot areas located in Ukrainian protected areas. Each of them boast clear and measurable outcomes. For example, due to rewetting of a drained swamp area in Roztochya Nature Reserve, wildfires don’t occur there anymore, the ground surface temperature has dropped.

The scientific knowledge and field experience of the Succow Foundation staff were summarized in lists of proposed protective measures and activities for different types of ecosystems, including wetlands. They can be used as guides in the prospective restoration projects in Polesia.

Rethinking the value of “healthy” wetlands

Wetland restoration is moving higher up on the agenda in Ukraine for a number of reasons. Wetlands of the Polesia were intensively drained mainly for agriculture production between 50th and 80th of the 20th century, which have changed the hydrological regime of the entire territory. It has led to degradation and thus in many cases abandonment of the lands, drop in groundwater levels, wildfires and droughts. Drained and degraded peatlands are sources of greenhouse gases. Particles emitted during wildfires are a dangerous air pollutant and got Kyiv to the top of the cities with the highest atmospheric pollution in 2020 and 2021.

At the same time, in their natural state wetlands mitigate the impacts of climate change due to their ability to absorb and retain carbon. When functioning properly, they protect people from extreme weather events by regulating the water flow. Wetlands serve as “kidneys of the landscape” accumulating and purifying water. The importance of Polesia’s water resources for Ukraine is immense.

Olga Denyshchyk, scientific project coordinator at the Succow Foundation

“Polesia is unique and fragile. Beyond its beauty, biodiversity, cultural and historical values, it holds the strategic water resources for the Dnieper, thus for the 2/3 of the Ukrainians who drink that water. I feel privileged to work in conservation and restoration of ecosystems. That is the best job I can imagine.”

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in the past year made Ukrainians recall another important role of wetlands, proven many times before in the course of history: barely passable, undisturbed mires and bogs serve as natural barriers against military invasion. Thus, restoration of drained wetlands in Polesia, in the vicinity to the northern border of Ukraine, would strengthen the natural defense line. Besides, natural hydrological regime of wetlands minimizes the risk of fires caused by shelling or explosions.

Turning wishes into plans

Now, when restoration of wetlands in Ukraine is likely to be supported by stakeholders, Frankfurt Zoological Society and the Michael Succow Foundation join their knowledge and experience to push this important work forward. The foundation’s experts are currently working on feasibility assessments for potential restoration sites in the Ukrainian part of Polesia, including Ramsar sites.

Anatoliy Smaliychuk, PhD in geography, GIS expert

“In my opinion, mire and old-growth forest ecosystems should be preserved and restored in Polesia foremost. Drainage and wood felling are the hurts that hardly could be cured completely. But we need to try, otherwise the natural landscapes we can observe now will be lost forever. Since the local culture and customs are closely interwoven with nature, they are under the risk of degradation as well.”

The complex assessment is expected to cover many aspects – from spatial, ecological and hydrological characteristics to legal status of territories and stakeholder analysis. This will allow the experts to determine the territories with the best prospects for successful restoration projects, plan practical restoration measures for each area and thus make our joint efforts for the benefit of Polesia’s wetlands as impactful and efficient as possible.

Top image shows a wetland in the Pripyat-Stokhid National Park in Polesia, Ukraine. Photo credit: Daniel Rosengren

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).

The year 2022: conservation wins in a year of trials

The year 2022: conservation wins in a year of trials

The year 2022 was a time of bitter trials for Polesia. Once known as a territory of precious nature, it turned into a battleground during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. As a result of the war in Ukraine, we had to revise our project since many activities became impossible in the current situation. And still, our numerous efforts undertaken in previous years bore fruit in 2022. In spite of the dramatic developments of the past year, some conservation results worth celebrating were still achieved.

Protected areas: greater size, stronger connectivity

36,000 hectares – this is the total area that gained legal protection through the creation of a new national park and a nature reserve as well as issuing protection passports for rare species’ habitat.

The year 2022 started with invigorating news: A decree issued by the President of Ukraine marked the official creation of the new Pushcha Radzivila National Park. The park protects a high conservation value area holding old-growth spruce forests, bogs and mires. Pushcha Radzivila, covering 24,265 ha , is home to more than 450 species of flora and 230 of fauna – dozens of which are nationally endangered. Among the national park’s inhabitants are Grey Cranes, Black Grouse, beavers, moose, lynx and various species of bats.

Bordering Rivnenskyi Strict Nature Reserve and Almany Mires Reserve, Pushcha Radzivila became an important link in the network of protected areas of Polesia. Through the designation of the new national park, the protection and ecological connectivity of the largest natural complex of bogs and transitional mires in Europe was enhanced.

Based upon field research conducted as part of the Wild Polesia project in 2020-2021, 142 habitat sites of rare species in Polesia were placed under legal protection. Their total area amounts to 6,372 ha. Forty two species now enjoy better protection, including mammals, birds, reptiles, insects, plants and fungi. Locating and mapping the space that species need to survive and securing this habitat through the “protection passports” plays a crucial role in bringing rare species protection into effect. This procedure envisages elaboration of scientifically grounded conservation measures for each single species (and sometimes even for certain habitat sites). These measures are mandatory, and their implementation is controlled.

Meanwhile, in February, 2022, the Almany Mires Nature Reserve got a new management plan for the coming 20 years. This was preceded by months of painstaking work that resulted in the list of scientifically grounded measures on conservation and support of valuable ecosystems, and of populations of endangered species of flora and fauna, as well as ensuring sustainable functioning of the nature reserve. It is expected that these measures will mitigate or eliminate the most significant threats to the ecosystems of the Almany Mires, such as climate change, drainage reclamation, wildfires, illegal wood felling, drying up of trees, road infrastructure development, spread of invasive species of flora and fauna.

Science for Polesia: long-term monitoring in the spotlight

The natural landscape of Polesia is shaped by the Pripyat – one of the few major European rivers that are still free-flowing. Advocates for Polesia’s wilderness focus on the need to maintain the natural state of the Pripyat as a key factor for the preservation of ecosystems and biodiversity in the whole region. This message was again reinforced by a study co-authored by Pavel Pinchuk from the project published in January 2022. Summing up the results of long-term monitoring carried out from 2001 to 2020, it proves that the natural hydrological regime of rivers is extremely important for Great Snipes during their breeding season.

Competing for a mate is extremely energy-demanding for lekking male Great Snipes. Therefore, rich feeding sites in close proximity to their breeding territories are essential for maintaining good physical conditions. Up to 90% of Great Snipes’ diet is made up of earthworms whose availability depends on the water level. Low water levels allows earthworms to disperse in a deep layer of soil. While, as the water table rises, they must congregate in a narrow layer of soil close to the surface. In this case, Great Snipes have easily available prey in abundance and their physical condition improves. At the same time, a further rise of water levels associated with flooding of the Great Snipes’ feeding territories leads to a decrease of the body condition of lekking birds. This is because the earthworms leave the flooded sites; their relatively short legs also don’t allow Great Snipes to wade in deep water. Thus, the birds have to expend much more energy, flying more often and further in search of prey.

The authors of the research highlight that the natural hydrological regime of the Pripyat with seasonal water level fluctuations is important for the preservation of lowland leks of the Great Snipe and, probably, of other species of waders breeding in the floodplains of Polesia’s rivers.

Another paper published in early 2022 looks into the unique case of wilderness restoration in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. The Chernobyl nuclear disaster (1986) was one of the worst man-made catastrophes in history. As a result of this tragic occurrence, in vast territories – previously densely populated and intensively used for agriculture – human activity ceased almost completely. The people who lived here up to 1986 had to relocate, the farmland was abandoned, and drainage canals were locked to prevent the spread of wildfires and contaminated water. As a result, a unique case of unguided nature restoration developed.

The long-term dynamic monitoring of landcover conducted in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone from 1999 to 2017 shows an impressive increase in wetland and forest areas. In parallel to this, species’ composition and population numbers changed too. The monitoring of diurnal birds of prey carried out from 1998 to 2019 proved that the Greater Spotted Eagle and the White-tailed Eagle – both wetland specialists sensitive to human disturbance that had been locally extinct in the study area – returned, and their numbers increased. At the same time, the scientists observed decreasing populations of birds of prey that prefer hunting in farmland. Interestingly, at the beginning of the monitoring, the population sizes of these species in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone were much higher than the regional average.

The study’s authors concluded that passive rewilding can bring European lowlands back to a near-natural state – at both an ecosystem and a biodiversity level.

Mapping the Polesia landscape

Another achievement by our scientists in 2022 is the elaboration of the first bespoke landcover map of the whole of Polesia. This became possible due to the meticulous work on bringing the results of large-scale field surveys into correlation with the data provided by a pair of Sentinel satellites. Google Earth Engine is used for information processing. The map identifies a set of landcover classes that can be detected from the satellite’s orbit, like farmlands and urban territories, water, deciduous and coniferous forests, meadows, bogs and mires. The tool allows experts to carry out various environmental analyses. For instance, the map enables dynamic monitoring of restoration or degradation of natural areas, changes in land use, and analyzing the intensity of seasonal floods in Polesia. The tool can also be of use for assessing landscape connectivity, mapping species distribution, or protected areas enlargement.

We hope that the year 2023 will be more favorable for one of largest and most valuable natural landscapes of Europe and its people. And we enter the new year eager to keep on working for the benefit of Polesia’s wilderness and the communities that call this impressive landscape home.

Top image shows the Pripyat river floodplain at sunset. Photo credit: Viktar Malyshchyc.

The project “Polesia – Wilderness Without Borders” is part of the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and is funded by Arcadia. The project is coordinated by Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS).